Economic Crisis and Resistance in Batticaloa, Eastern Sri Lanka

Thavarasa Anukuvi

Introduction

The question whether ‘the people’ of the North and East should or could protest in solidarity with the #GotaGoHome protest movement has been the subject of much debate (Pundir & Kanapathippillai 2022; Sandranathan 2022; Ellis-Petersen & Sandran 2022; De Soysa 2022; De Sayrah 2022). Since the end of the war, people in the North and East have been waging long-standing struggles —for fundamental rights, against systematic discrimination, communal attacks against minority communities, for justice, accountability, sustainable peace, and ongoing resistance against militarisation and land occupation in the North and East of Sri Lanka. Moreover, it’s worth noting that it is not the first time people in the North and East have experienced scarcity of food and essential items. During the 26 years of civil war, and particularly during the last phase of the war in 2009, people in the North and East have experienced severe food, fuel, and medicine shortages (Sandranathan 2022). Against this backdrop, in this article I explore the response of people in Batticaloa to the #GotaGoHome protests and share some insights gained from shifting the focus from Colombo to Batticaloa. This essay draws on my personal experiences, open-ended discussions, and participant observations of protests between January-July 2022. The photos included in this essay illustrate people’s resilience and a particular form of resistance in Batticaloa, which resonates with the ambivalence and diverse positionings vis-à-vis the #GotaGoHome movement, and can be seen as a continuation of civil society protests in the district.

Batticaloa

Batticaloa district consists of a multi-ethnic and multi-religious social fabric, with Tamil and Muslim communities forming the majority. The social structure is further refracted by a complex class system which is intersected by caste, ethnicity, and gendered hierarchies as well as other stratifications. In addition, decades of civil war and persisting inter-communal conflicts disclose various social, economic, and political histories, making this region a complex socio-cultural and political terrain.

I have lived both in Batticaloa town and in my home village, Pavatkodichchenai, that is located in the Vavunativu Divisional Secretariat division, the poorest in the district. During the civil war, people in the district experienced severe food and medicine shortages. Following the years of civil war, the resilience of people in Batticaloa and their distinctive ways of handling economic burdens come as no surprise. This experience has helped different groups of people come to terms with the current economic crisis more easily than in other parts of the country. Scarcity of milk powder, gas, and continuous power cuts in the district did not bring people to the streets, and this is still applicable to many people in the district.

Thus, during the initial stage of the economic crisis, although many discussions took place and concerns were articulated in private spaces, the streets in the district remained largely silent. However, it was after the Mirihana incident of 31 March, where hundreds of people demonstrated near former President’s Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s private residence on Pangiriwatte Road near Kotte in the Western Province demanding his resignation, that a number of protests in solidarity with the #GotaGoHome movement were organised in Batticaloa.

On 4 April, Eastern University medical faculty students held a demonstration at the Kallady bridge and in front of Gandhi Park—two important landmarks in Batticaloa. Tamil National Alliance (TNA) MP Rasamanickam Shanakiyan also joined the protest and led a march under the slogan #GoHomeGota to the house of Sivanesathurai Chandrakanthan (‘Pillayan’), MP of the Tamil Makkal Viduthalai Pulikal (TMVP) that is part of the governing Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) alliance, to demand his resignation from all government positions. On 7 April, I witnessed a group of women holding another demonstration at Gandhi Park demanding reductions in the prices of essential goods and for the State to provide relief to vulnerable communities in the country.

On 8 May, students of Eastern University and a few local public organisations led a rally from Eastern University to Chenkkallady junction. They set up a #GotaGoGama shelter and stayed day and night in solidarity with the GotaGoGama occupation at Colombo’s Galle Face Green, demanding the government to ‘Go Home’. According to a participant, this protest was sustained for 20 days, but subsequently discontinued due to State intimidation. In the meantime, the appointment of new government ministers on 18 April 2022, including three out of five parliamentarians from Batticaloa district – Naseer Ahamed from the Sri Lankan Muslim Congress, Sivanesathurai Chandrakanthan from TMVP, and Sathasivam Viyalendiran from SLPP – further intensified people’s anger towards the government. Following the appointments, people in Eravur, Oddamavady, and Kalmunai led demonstrations against these ministers as they were continuing to prop up an unpopular regime. It is noteworthy that the protests were predominantly organised by Muslims, who insisted that Naseer Ahamedshould resign from his ministerial post as he was elected on the ticket of the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress, which campaigned in alliance with the Samagi Jana Balawegaya in opposition to the Rajapaksas at the 2020 general elections. In addition, each time the national trade unions called for a strike, different Batticaloa trade unions such as the university lecturers’ union, the teachers’ union, the bank union, and the Batticaloa journalists’ union, supported it, calling on the government to resign.

Following these demonstrations and public forms of protest in solidarity with the #GotaGoHome movement, civil-society organisations in Batticaloa such as women’s organisations, human rights activists, social activists, and members of inter-religious groups commenced a series of dialogues on the unfolding situation. I was part of the organising team and participated as a researcher in every discussion. These discussions were held in the space of a civil society organisation in Batticaloa and were aimed at fashioning a local response and method of engagement with the national developments. In these discussions, the participants reflected on their experiences of the economic crisis and shared their thoughts on what could be the Batticaloa people’s role in the #GotaGoHome movement.

Many participants in these discussions linked the current crisis with the democratic struggles of Tamil and Muslim people in Batticaloa through different modes of resistance and struggle such as peace walks, art works and more, in the past. The discussions also foregrounded Tamil-Muslim relations, like the tension between these communities, and how people ignore each other’s problems while living alongside each other. Participants further added the importance of paying attention to women-headed households and other vulnerable communities, and how the economic crisis impacts them, as well as the State’s systematic oppression of ethnic minorities in the North and East of Sri Lanka. Overall, many participants emphasised that the local communities’ response should highlight ‘local’ issues of people in the district for democratic change in Sri Lanka.

Batticaloa’s Justice Walk

The statue of Gandhi in the Gandhi Park overlooks a poster that reads: “We want a non-violent home and country”.

On 12 May, after a government-led mob attacked #GotaGoGama at Galle Face in Colombo on 9 May, and violence spread across the island, people in Batticaloa initiated the #JusticeWalk. It is still continuing as of end-September. The #Batticaloa Justice walk is the focus of my essay as it sheds light on different voices from Batticaloa district and adds a perspective on the #GotaGoHome movement from Batticaloa. In contrast to other protests in Batticaloa during the economic crisis described above, the Batticaloa Justice walk is neither politically partisannor institutionally organised. Those participating do so as individuals, not as members of any organisations or political parties, nor as representatives of groups. Moreover, the Justice walk does not seek to replicate the #GotaGoHome protests, but aims at building solidarity for democratic change in the country by highlighting ‘local issues’ through a form of resistance that has been deployed by activists, women’s groups, and individuals in Batticaloa throughout the war and post-war eras. An in-depth exploration of the Justice walk’s consistency, its particular form and atmosphere, participants, and their demands allows us to shift the perspective from an angle on Batticaloa to an angle from Batticaloa with regard to the GotaGoHome movement. To recalibrate the viewpoint in this way, and to emphasise the distinctiveness of the Justice walk is not to devalue other forms of protest; rather, this essay aims at making a case for recognising the diversity of resistance, including less visible, quieter, and locally rooted modes, and their dynamic, and at times ambivalent, relation to the #GotaGoHome movement, inspired by different histories and experiences.

The Justice walk connects two significant landmarks in Batticaloa. The walk starts from St. Sebastian’s Church, whose eastern point faces the Batticaloa lagoon, where the Kallady bridge crosses. It ends at Gandhi Park which is located near the Batticaloa clock tower in Batticaloa’s city centre. These two landmarks are connected by the Batticaloa-Kalmunai road, which is Batticaloa’s main road. The distance between these two points is about 1.5 km. The road takes you past GV hospital, Arasady clock tower, and Batticaloa police station until it reaches Gandhi Park in about an hour. The Gandhi statue is a well-known place, and many public gatherings and protests have taken place at the site. It is unofficially marked as Batticaloa’s ‘agitation area’.

Those who want to participate on a given day arrive at St. Sebastian’s Church between 845 and 915 in the morning. The walk begins at 915 am. Participants do not speak during the walk. The walk begins and ends with a meditation. However, the noise from the two busy roads—the Batticaloa-Kalmunai and Lady Manning Drive road on the east side of St. Sebastian’s Church – contrasts with the silence during the walk. Yet due to the fuel crisis, the streets at times became completely deserted, and the serene sounds from the lagoon enveloped the space. According to my experience, meditation helps protesters to mentally and physically prepare for the day. Protesters do not talk much before starting the walk. People mostly connect with each other through smiles and silent greetings. Once the meditation ends, and before starting the walk, one of the protesters briefly describes the purpose and the process of the walk for newcomers. As it is monsoon off season, even the morning sun is a bit hard to bear at times, but the wind from the lagoon brings some relief amid the harshness of the heat.

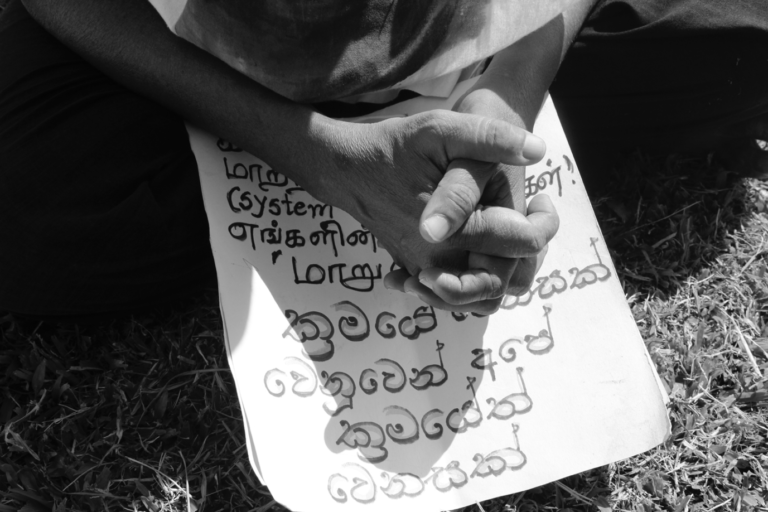

A participant sits after the Justice walk in silence at Gandhi Park.

People participating in the walk come with diverse demands, reflecting their feelings, opinions, and aspirations in relation to larger, structural issues such as economic hardships as well as long-standing problems such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act, memorialisation of the war, and land grabbing in the North and East of Sri Lanka. Some people bring with them banners made at home, while others may prepare their posters at St. Sebastian’ Church. In general, the posters and banners reflect on peace, justice, democracy, local knowledges, the impact of the economic crisis, and structural issues in the country. Some of these demands and slogans overlapped with the #GotaGoHome movement. This included the demand of Gotabaya Rajapaksa to resign, yet this was one demand amongst many others. Following are some of the slogans I have documented, which highlight the wide range of demands, aspirations, and hopes of Batticaloa protestors: ‘Abolish the Executive Presidency’, ‘Walking for peace’, ‘Remembering May 18’, ‘Looking for a society free of corruption’, ‘Do not steal our local resources’, ‘Unite against power, dominance, and oppression’, ‘Wanting a people’s constitution’, ‘Wanting a constitution to protect the life of the future generation’, ‘வன்முறை வீட்டிலும் வேண்டாம், நாட்டிலும் வேண்டாம்; (We don’t want violence in the family and country’), ‘நான் நானாக இந்த நாட்டில் வாழ வேண்டும் (I want to live as I am’), ‘System change’, ‘Let’s protect everyone’s rights in the country’, ‘உயிர் வாழும் உரிமை’ (‘Right to live’), ‘We want our rights back’, ’No corruption’, ‘Protect our local resources’, ‘Give us our money back’, ‘We want education for knowledge and morality’, ‘உணவும் இல்லை, உறவும் இல்லை, (‘Do not have food or relations’), ‘No Prevention of Terrorism Act’, ‘Have an accountable government’, ‘I walk for the government to do its job’, ‘The government should be held accountable for this crisis’, ‘We want space to express ourselves without any fear’, ‘நீதி, பொறுப்புக்கூறல், நிலையான எதிர்காலம், (‘Justice, accountability, and sustainable future’), ‘Pave the way for the next generation not to carry this burden’, ‘Right to remember’, ‘Stop militarisation and the illegal occupation of lands in the North and East’, ‘பெண்களையும், இயற்கையையும், சக மனிதனையும் வன்முறைக்கு உட்படுத்தாத வாழ்விற்க்கான நியாயப்பயணம் (‘Justice walk for a life style that does not violate women, nature, and fellow human beings’). The slogans were written in Tamil, Sinhala or English. Several of them deployed a general verb form without the use of personal pronouns, e.g. ‘walking for peace’ instead of ‘I am walking for peace’ or ‘remembering’ instead of ‘i/we remember’. In my understanding, this depersonalised way of articulating demands and aspirations, without a personal pronoun, is a way of safely navigating experiences and histories of violence and oppression of protest by going beyond the individual.

The pattern of everyday walking is the same, but all days are not the same in terms of the atmosphere, sounds, number of participants, and weather. The everyday walk differs in terms of timing depending on the people who lead the walk, but the Batticaloa clock tower never fails to remind us of the walk’s timing. The 10 o’clock bell usually rings when the demonstrators are about to reach Gandhi Park. During the usually busy morning hours the walk passes banks, petrol stations, police stations, restaurants, and dozens of shops. People on the street are now used to the walk and faces are now mutually familiar to both parties. The walk has become an ordinary occurence for people in the shops and on the street. A demonstrator told me that whenever she fails to come for the walk, the shopkeepers notice her absence and ask her about it the next time. Every time, the shopkeepers smile at the demonstrators and share many stories. On many occasions I observed how they connect the walk with the broader political scenario in Sri Lanka. Sometimes they say, “You people are walking every day, but things remain the same in the country.” On another day, a woman observing the walk told me: “You are walking for us, but many people are not participating in the protest. In the end, we will all get the benefit of your hard work.” Time feels almost suspended during the walk.

The large number of women participating in the Justice walk is noteworthy. This builds on a long history of activism of women’s organisations and passionate individual women working as frontline activists and contributing to many democratic efforts. For instance, similar peace walks in Batticaloa began in 1995 when a group of women walked in Batticaloa city and held a silent sit-in near Batticaloa Gandhi Park for peace and justice when violence was unleashed everywhere in the district, and emergency laws and curfew were imposed (Maunaguru 2016: 27). And in 2014, when tensions between Muslim and Tamil communities were rising in the aftermath of the Aluthgama attacks, Muslim and Tamil women walked to different religious sites, asking for nonviolence and peace (Emmanuel 2022). Similarly, the Suriya Women’s Development Centre, the Non-Violence Support Group, the Batticaloa Peace Committee, and family members of the disappeared have been continually raising their voices against injustice and for peace, often at great personal risk. The current Batticaloa Justice walk is also predominantly led by women.

When the protest began, the Criminal Investigations Department frequently came in civil clothes to Gandhi Park, asking questions such as ‘Who is organising the walk?’, ‘What is the purpose of the protest?’, and ‘Are there any political parties involved in the protest?’ However, the hope is that this form of resistance gives more leverage when negotiating with the police or the civil administration. One day, there was a massive crowd at a petrol station and a clash between police and people waiting in the queue erupted. The Justice walk had to pass through the scene. The police calmed everyone down for a while and made space for us to walk. The police may be more comfortable with tolerating this particular form of resistance.

The Justice walk navigates through petrol queues.

Justice Village – நியாய கிராமம் – යුක්ති ගම්මානය

As a part of the Justice walk, the demonstrators have begun to organise an event every Saturday at Gandhi Park, the final destination of the walk. It is, unlike the walk, a space for talks, discussions, theatre performances, exhibitions, poem readings, teach outs, and songs. Batticaloa’s Gandhi Park is located in the middle of the city, thus many people come to the place to relax and watch the beautiful sunset in the evening, which makes for a great audience. A play called Eluttaani, performed on 4 June by a group of demonstrators, narrated for example the skills and knowledge of Batticaloa’s local culinary culture as a means of dealing with the economic crisis in the district. On another Saturday, some demonstrators performed a Kuththu, a popular, traditional Tamil theatre form, conveying useful information about the current situation. Paintings and installations are another important part of the Saturday events at Gandhi Park. They highlight the importance of remembrance, of addressing gender-based violence, and local knowledge.

Children are a crucial part of the ‘Niyayakiramam’ (Justice village) as participants in the walk refer to its final destination, Gandhi Park, and the justice walk. At Gandhi Park, they would draw, sing, and dance for the struggle. Every Saturday, the demonstrators make giant banners with slogans collected from the previous seven days of the Justice walk. This collective activity unites people and provides an opportunity to reflect on and document the protest. Many people who do not participate in the Justice walk also come to the site, watch performances, and sometimes start conversations with the organisers by asking about the events. The conversations centre on sharing each other’s unique experiences of the crisis and expressing feelings. I could observe that the people who gather at the site are individuals but connected through different fields like art, activism, and social work. The demonstrators are also willing to actively reach out to the people in the park. For example, one day, the demonstrators approached the people present with a piece of painting and built a conversation around the work. In this way, protestors involved the public in the struggle.

On a Saturday afternoon, children compile slogans from the week at Gandhi Park.

The demonstrators often state on their social media platforms and banners that the demonstration space is an open call for everyone who respects the values of democracy, peace, and justice. People join the protest from all age groups, different ethnic communities and economic classes, and different areas of the district. A participant explained this as follows: “We are friends walking for peace and justice. The walk gives us aaruthal (consolation) in this catastrophic situation. We are frustrated with this scenario and want peace in our bodies. So, we are walking rather for us than others.”

Closing Observations

Based on my participatory observation and open-ended discussions with residents of Batticaloa district, I would like to highlight a few points about how people in Batticaloa district related to the #GotaGoHome movement.

First, people’s protests in the district demanded not just solutions to the economic crisis. People participating in the Justice walk, as well as those participating in the #GotaGoHome movement anticipated structural and constitutional changes for a new chapter in the country, where they can live freely. My discussions with family members of the disappeared, human rights activists, and social activists in the district, some of whom have participated in the Justice walks, highlight many examples of how State actions against minority communities continue even amid an economic crisis. Land occupation by the Sri Lankan navy in Vattuvakal and the Buddicisation of the Kurunthurmalai Hindu temple in Mullaitivu District by the Archaeological Department are very recent examples of this. Many years of armed conflict and militarisation have absorbed a large amount of gross national income (Satkunanathan 2022). Thus one can conclude that the collective anticipation from Batticaloa is that without a proper vision for the long standing ethnic issues in the country, it will be challenging to make a collective effort to change Sri Lanka for the better. A senior human rights activist in Batticaloa told me, “we have suffered a lot in the last 30 years of civil war in the country; thus, this economic crisis will not kill us. So, our tākam (thirst) is not for food. We need equal rights like others in the country.” In contrast, I have witnessed many people expressing how badly the economic crisis is affecting them. My understanding is that this is part of a larger concern with long-standing histories and experiences of injustice, rather than viewed as an insulated economic problem. Thus, while it is important not to neglect the dire economic impact of the crisis in many places in the North and East of Sri Lanka (Srinivasan 2022; Fonseka 2022), it is equally important to look at them in conjunction with issues of oppression and violence that people in the district continue to experience.

Second, while it may be true that people in the North and East have been ambivalent about participating in the #GotaGoHome movement, this does not mean that they endorse the SLPP government or Gotabaya Rajapaksa. My observations and discussions with people in Batticaloa reveal that many people do not have much hope and trust in the movement. Family members of the disappeared and activists’ primary question is: “What comes after the movement in terms of solving the issues faced by minority communities in the country?” Many of my interlocutors also alleged that they have been engaged in these democratic struggles for decades, but even in the post-war situation, there was not much support for their struggle from the Sinhalese community. Others also pointed out that they felt that there were no promising demands emerging from the #GotaGoHome movement to address the ethnic issue in the country. Against this backdrop, my interlocutors underlined that for them, it is a huge move to take part in such protests. In addition, surveillance, intimidation, and inhuman laws like the PTA suppress minorities’ voices and make them more vulnerable. Thus, silence on this count can be read as a collective expression of reluctance, historically constructed through varied forms of repression and fear (Castillejo-Cuellar 2013: 20). Hence, people have developed silence as a form of resistance and for survival, and their reluctance to take part in the #GotaGoHome movement can be analysed as an expression of knowledge learned from the collective past of loss, pain, and disappointment. This past cannot be ignored, and one has to deal with the past to build solidarity in the present.

Thavarasa Anukuvi is an independent researcher and photo-journalist based in Batticaloa.

References

Castillejo-Cuellar, Alejandro. (2013). “On the Question of Historical Injuries: Transitional Justice, Anthropology and the Vicissitudes of Listening.” Anthropology Today, 29(1): 17–20.

De Soysa, Minoli. (2022). “Fear in the East: What Lies Beneath.” Groundviews (1 August). Accessed 05.10.2022. Available at https://groundviews.org/2021/04/16/fear-in-the-east-what-lies-beneath/

De Sayrah, Amalini. (2022). “Why Minorities Must Support the Struggle.” 2022. Groundviews (5 May). Accessed 05.10.2022. Available at https://groundviews.org/2022/05/05/why-minorities-must-support-the-struggle/

Ellis-Petersen, Hannah, and Rubatheesan Sandran. (2022). “‘We Want Justice, Not Fuel’: Sri Lanka’s Tamils on North-South Divide.” The Guardian (22 June). Accessed 05.10.2022. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jun/22/sri-lanka-tamils-protests-economic-crisis

Emmanuel, Sarala. (2022). “The Batti Walk for Justice: A Resistance for Fundamental System Change.” The Morning – Sri Lanka News (30 July). Accessed 05.10.2022. Available at http://www.themorning.lk/the-batti-walk-for-justice-a-resistance-for-fundamental-system-change/

Fonseka, Ruwani. (2022). “Feminist Collective for Economic Justice Releases Statement on Sri Lanka’s Economic Crisis.” The Morning – Sri Lanka News (6 April). Accessed 28.09.2022. Available at https://www.themorning.lk/feminist-collective-for-economic-justice-releases-statement-on-sri-lankas-economic-crisis/

Maunaguru, Sitralega. (2016). “Times of Passion in Times of Repression: 1975-2003”. In Sitralega Maunaguru & Marilyn Weaver (Eds.). Kootru (27-39). Batticaloa: Suriya Women Development Centre.

Pundir Pallavi, Kanapathippillai Kumanan. (2022). “Why These Women Aren’t Joining Sri Lanka’s Massive Anti-Government Protests.” VICE World News (1 August). Accessed 28.09.2022. Available at https://www.vice.com/en/article/n7n8jx/tamils-sri-lanka-protest-rajapaksa-crisis

Sandranathan, Rubatheesan. (2022). “Why No Protests in the North? War Time Survival Techniques Back in Use.” The Sunday Times (1 August). Accessed 28.09.2022. Available at http://www.sundaytimes.lk/220417/news/why-no-protests-in-the-north-war-time-survival-techniques-back-in-use-479813.html

Satkunanathan, Ambika. (2022). “Sri Lanka in Crisis: Why the Past Lives on in Its Collective Future.” 9DASHLINE (2 August). Accessed 28.09.2022. Available at https://www.9dashline.com/article/sri-lanka-in-crisis-why-the-past-lives-on-in-its-collective-future

Srinivasan, Meera. (2022). “In Search of Livelihoods and Loved Ones.” The Hindu (17 June). Accessed 28.09.2022. Available at https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/in-search-of-livelihoods-and-loved-ones/article65537325.ece