On the Edge: University Education in Sri Lanka by Kaushalya Perera

At the COP-28 Climate Change Conference in Dubai in December 2023, Ranil Wickremesinghe announced the establishment of a Climate Change University in Sri Lanka. In the 2024 Budget Speech, Wickremesinghe also promised to establish eight new State universities. Is this even a possibility? To assess that, one must take stock of how public resources have been disbursed to both State and private universities in recent times, together with popular perceptions of university education, State policies on higher education, and the economic crisis. Here, I discuss recent resource allocations to State universities as well as private universities.

Some context first.

In 2022, during the Budget Speech, Ranil Wickremesinghe said that “it is necessary to examine whether all sections of the society are receiving equitable benefits through health services and free education that is currently provided” (6).[1] The year after, in 2023, he said that Sri Lankans are not benefiting from free education fully, and to this end, “a series of comprehensive reforms will be undertaken” (157).[2] In both instances, he then proceeded to propose a severely stunted budgetary allocation for education.

Wickremesinghe is only the latest in a long line of public representatives to malign State universities[3], which they have done as a precursor to reducing resources for that sector. Tellingly, despite changes in government, the rhetoric in the argument for defunding State universities has not changed, which makes it State policy. For at least two decades, a systematic campaign has been conducted by successive governments to portray State universities as inefficient institutions that house violent agitators.

Since 2012, for example, two contradictory tropes regarding undergraduates of State universities have been circulating in both Sinhala and English newspapers. On the one hand, undergraduates are naive victims of third parties with political agendas. On the other, they are violent agitators rampaging in the streets and damaging everything in sight. Through both narratives, universities are portrayed as lawless spaces, conveying the idea that academics were not ‘doing their job’ or administrators are ‘weak’ (Perera 2018). Such portrayals are important in building a negative image of State universities, and a discourse that State universities are a waste of public funds. Such public perceptions have helped justify successive governments’ support for the privatisation of higher education.

To tease out the ways in which privatisation of higher education entangles these different types of institutions, this essay focuses on three factors: resource allocation to State universities; State-support for private higher education institutions (HEIs); and the loan-driven policy environment.

State Universities and Disappearing Resources

Allocations for the education sector as a percentage of Sri Lanka’s gross domestic product (GDP) have been consistently low. According to the ‘Report of the Select Committee of Parliament to make suitable recommendations for the expansion of higher education opportunities in Sri Lanka’ (2023) (hereafter referred to as the Parliamentary Select Committee Report)[4], resource allocation came down to 1.5% of GDP in 2022 from the already low rate of 2% in 2015 (25). This allocation includes funds for primary and secondary schools, teacher salaries, vocational and technical colleges, teacher education colleges, national examinations, student uniforms, and other categories, as well as allocations for State universities under the Ministry of Higher Education, and research in State institutions.[5]

Further aggravating the situation is the fact that allocations are illusory: the amounts allocated are not always released. In the year 2022, public universities were allocated 51,115 million LKR (in recurrent costs) and 3263 million LKR (in capital costs). Of the latter, universities only received 2259 million LKR.[6] Some universities have not been allocated any funds for capital expenditure, such as the Eastern University for 2022, and the Open University of Sri Lanka for 2023. Funds for universities include recurrent expenditure (staff salaries, maintenance of premises), hostel management, research funds, and capital expenditure.

Capital fund allocation is what finances new programmes, new premises and infrastructure, and other such development activities in universities. When capital allocations are reduced, it gives the lie to promised new projects in a budget speech. When capital allocations are not made, a ‘Climate Change University’ exists only in the imagination.

Yet, State universities are expected to do more, with reduced resources. As we see in Table 1 below, while the number of students enrolling in State schools has remained relatively consistent, the student intake to the universities administered by the UGC has increased nearly five times since 1995.

Table 1: Number of students in general and university education 1995-2021

(Source: University Grants Commission 2021, adapted from p. 2)

It is eminently clear then, that public universities are expected to provide a ‘quality’ education for five times as many students. The question is, how? As per the Parliamentary Select Committee Report, the State assumes that the shortfall in State allocations and resources can be bridged by the private sector and through funds produced by the universities themselves (termed ‘generated funds’), which would allow the State sector to operate as before.

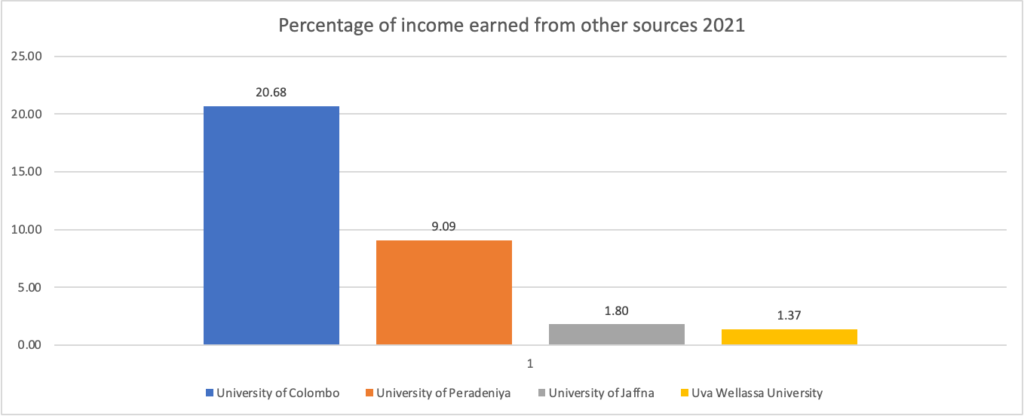

Leaving aside the mandate of the State to provide education for its citizens, this disregards at least two concerns. First, universities generate funds mainly by offering fee-levying courses to outsiders (e.g. weekend courses, postgraduate programmes, etc). This drains the time and energy of academic staff from honouring their primary commitment, i.e. the education of undergraduates and research. Secondly, it does not take into account the disparate abilities of State universities to generate such funds. Urban universities are far better placed for instance, to attract the public to their weekend or evening courses, and older (or more reputed) universities have more power to attract post-graduate students. Table 2 clearly demonstrates this disparity.

Table 2: Percentage of income earned via non-State sources by selected universities

(Source: University Grants Commission 2021)

Invisible State Resources for Private Universities

The rhetoric of the current and previous governments ignores the crises facing State universities and instead focuses on the purported wonderful results that private higher education would bring to the country. It presents the expansion of the private higher education (HE) sector as a strategy for stemming the outflow of funds of Sri Lankans, and as a means of attracting new foreign currency. A number of policy recommendations including the Parliamentary Select Committee Report and the National Education Commission (NEC) framework (2022) strive to develop a framework in a concerted effort to subsidise private education through concessionary taxes and access to State resources.

The Parliamentary Select Committee Report includes many recommendations to expand private HE at both the institutional and individual level, but has no corresponding growth recommendations for the public HE sector.[7] It also illustrates the shift in the government’s approach, from extending institutional support to individualising responsibility. By proposing initiatives where individuals secure resources for themselves, the State encourages institutions whose funding is contingent on the money such individuals bring. In other words, it is up to the individual to locate funds for their own education; and to institutions to attract these entrepreneurial students with their own funds, so that the State can divest itself of its responsibilities.

As encouragement for the expansion of private HE, successive governments have made public resources available to private education providers in a number of ways, as listed below:

- Budget allocations for student loans: this is a programme which encourages students registering at private HE institutions to apply for a loan from a State bank. In 2021, the government allocated money for 3701 student loans, amounting to 2.8 billion LKR. The 2023 budget allocated 1029 million LKR for the same. The State absorbs the interest payment for this scheme. From 2017 to 2022, the State paid the interest on loans taken by students following degrees at 17 private HEIs, including the Sri Lanka Institute of Information Technology—SLIIT (Malabe), National School of Business Management—NSBM (Homagama), Saegis Campus (Nugegoda), and Royal Institute (Colombo).[8]

- Land and money for private HEIs: An initial amount of 500 million LKR and 25 acres of land was taken from the Mahapola Trust in 1988 for SLIIT, with the agreement that it would continue to be a State entity and ultimately become a part of the University of Moratuwa (COPE 2021).[9] Subsequently, State claims on it were systematically removed in a manner that was neither procedurally correct nor transparent.

- State sector professionals in private HEIs: this is an inadvertent result of the lack of regulation. The National Education Commission (2022) report states that many UGC approved private HEIs obtain the services of State university lecturers.

The lack of oversight on companies that offer educational services—which is what private HEIs are—has allowed them to enjoy impunity from accountability, and to exhibit varying quality and facilities for students.

Governments seem to have expected that subsidising the private HE sector, offering incentives for commercial engagements as sources of revenue, and encouraging the use of private funds by individuals and families to finance students’ higher educational needs would solve their problem, i.e. fulfil such demands from the electorate.

These arguments are flawed on multiple levels. The most problematic issue is a lack of oversight and transparency on subsidies and resources that are provided to the private HE sector. The public assumes that investments in such HEIs are entirely private. An additional consequence is that waste or corruption in that sector have not been addressed. There is an assumption that if the private institution is not-for-profit, the problems generally associated with private education would be mitigated (that they would operate ethically, be equitable, and have little effect on public institutions). In the USA, for example, the so called ‘Ivy League’ universities are private not-for-profit ventures, and are considered to put learning above profit. A for-profit university, such as the majority of Sri Lanka’s private HEIs, needs to focus on revenue, which may be at the cost of quality of learning and teaching.

Secondly, such arguments hide how the burden of funding is almost entirely shifted to the individual citizen, consequentially reducing the State’s responsibility to educate its citizens. Considered in conjunction with the reality that State resources are being channelled to establish and sustain private HEIs, this becomes a grave moral concern.

Thirdly, State officials imply that the money spent on the private HE sector feeds the Sri Lankan economy, which is misleading. Private HEIs provide degrees and professional qualifications from foreign institutions and are costly. For example, the average cost to the State for an engineering degree is roughly 700,000 LKR (as per the Parliamentary Select Committee Report) compared to an electronics and electrical engineering degree at SLIIT, which costs approximately 3 million LKR (according to its website[10]). A large proportion of the fees of private HEIs and individuals attending it are credited to foreign institutions, for their certification of qualifications, registration for examinations, etc.

In addition to reducing money for the higher education sector, successive governments have also taken loans from international financial organisations to fund universities, which has affected independent policy-making as discussed in the next section.

State Policy Driven by Foreign Money

Another significant issue is the loan money that is hidden within ‘national’ budgetary allocations. Since 2017 (and possibly earlier), loans and grants taken from various foreign entities are included in the annual budget. In the 2023 and 2024 budgets, the following were listed as sources of funds for the education sector:

- Countries: India, Kuwait, Norway, the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, Germany, Australia.

- Bilateral and Multilateral Development Organisations: The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the Korean International Cooperation Agency (KOICA), the Korea Economic Development Cooperation Fund (EDCF), USAID, and the Erasmus Fund of the European Union.

- United Nations Organisations: UNFPA, UNICEF, UNESCO.

- International Financial Institutions: The World Bank, the OPEC Fund for International Development (OFID), the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Therefore, the ‘national’ budget currently includes notes on specific foreign monies, as well as loan/grant project information. Under the ‘Higher Education development project’ sub-head, for instance, of the total projected spending of 24,385,000 million LKR, foreign loans amounted to 15,670,000 million LKR, whereas domestic funds were only 6,675,000 million LKR.

When the budget allocation is loan-derived, policy too is driven by foreign entities. Loan or grant conditionalities make it difficult to change policies as necessary. The World Bank’s ideology that higher education should be privatised informs some of the policies enacted in State universities in the last three decades. The three loan cycles were vehicles for the entry of quality assurance mechanisms, while the last loan cycle introduced ‘University Business Cells’ to all state universities. Through these two mechanisms, State universities have become part of a ranking system which is based on numerical measures of quality, rather than qualitative measures of learning and teaching. Research is seen as a phenomenon that can be ‘commercialised’, which is detrimental mostly, but not only, to the humanities and social sciences which typically produces research that may not directly lead to commercial or profitable ventures.[11]

Shifting the Burden from State to Citizen

The state’s strategic policy on higher education shifts the burden of spending on higher education to the citizen, along with a rhetoric of blaming the victim, i.e. framing the education sector itself as being at fault for not producing graduates who are suited for the country’s needs.

‘National needs’ is a problematic concept given that in the past few decades, this has largely been driven by electoral policies of successive governments (e.g. Mahinda Chinthanaya). The general policy approach appears to be that Sri Lanka is a middle-income country and needs science and technology graduates (see NEC report) but beyond this, there seems to be no specific vision for education. Low resource allocation for State universities and encouragement of private HEIs, however, does not cohere with any vision for a developing economy.

There is tragi-comedy in anticipating more and more with less and less, as successive governments have come to expect of State universities. How can better teaching and research come about in a context of less financial allocations and increasingly less time in the hands of academics (a result of ‘reforms’ aligned to quality assurance)? The situation has become even more aggravated in the present economic meltdown. Indicators show that poverty and malnutrition rates are high, and interrupted education (in the form of dropouts or sustained absenteeism) is also high at all levels of education. None of this is considered in the defunding of State universities.

Governments have harped on the need for all citizens to access higher education, the requirement for more ‘efficiency’ in education systems (both at school and tertiary level), and the urgency to change education to suit the global economy. Yet the dangers of exclusively catering to a global market in which Sri Lanka is a peripheral economy are rarely reflected upon. The history of our dependent economy, and those of other developing countries, should already illustrate how unwise this exclusive focus can be.

What is starkly apparent is that there is no long-term vision of education, from primary to tertiary, and that today, there is even less commitment to public education than before. Expanding higher education opportunities in the country is definitely a pressing need; but one that is better, and more equitably addressed through greater investment in and corresponding expansion of the public system of higher education, rather than its private counterpart.

Acknowledgements

This article draws from ongoing work for a situation report by myself, Shamala Kumar, and Ahilan Kadirgamar. We are grateful to Vishvika Selvaraj and Madhulika Gunawardena for sourcing data.

Kaushalya Perera (PhD, Pennsylvania State University) is a Senior Lecturer at the Department of English in the University of Colombo, and a member of the ‘Kuppi Collective’.

Image Source: https://bit.ly/42AfQGs

References

COPE. (2021). “Special Report presented by the Committee on Public Enterprises” (Second Report of the Committee on Public Enterprises), Ninth Parliament, first session. Available at https://parliament.lk/uploads/comreports/1617702223080560.pdf#page=1

Gunawardena, Chandra and Rasika Nawaratne. (2017). “Brain drain from Sri Lankan Universities”. Sri Lanka Journal of Social Sciences, 40 (2): 103–118. Available at https://sljss.sljol.info/articles/10.4038/sljss.v40i2.7541

National Education Commission. (2022). National Education Policy Framework (2020-2030). Available at: https://nec.gov.lk/national-education-policy-framework-2020-2030/

Perera, Kaushalya. (2018). “The Sri Lankan undergraduate in the Sinhala press”. Kalyani [Journal of the University of Kelaniya], XXXII: 83–107. Available at https://kalyani.sljol.info/articles/10.4038/kalyani.v32i1-2.28

University Grants Commission. (2021). “Sri Lanka University Statistics”. Available at https://www.ugc.ac.lk/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2404%3Asri-lanka-university-statistics-2021&catid=55%3Areports&Itemid=42&lang=en

Notes

[1] Wickremesinghe, Ranil. (2023). Budget Speech. Available at https://parliament.lk/en/budget-2023/budget-speech-second-reading-of-the-appropriation-bill

[2] Wickremesinghe, Ranil. (2024). Budget Speech. Available at https://www.treasury.gov.lk/web/budget-speeches/section/2024

[3] By ‘State universities’, I mean the 17 public-funded degree-awarding higher education institutions regulated by the University Grants Commission (UGC).

[4] Report of the Select Committee of Parliament to make suitable recommendations for the expansion of higher education opportunities in Sri Lanka, Volumes 1 & 2 (2023). Parliamentary series No.100. Available at https://parliament.lk/uploads/ comreports/1689939464085452.pdf . The Committee included 13 members of Parliament who invited various sectors of the public for discussions.

[5] In addition to the 17 universities under the UGC, this includes the Bhiksu University, the Buddhist and Pali University, and the University of Vocational Technology. It does not include the General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University (under the Ministry of Defence) nor the Ocean University (under the Ministry of Skills Development and Vocational Training).

[6] Information obtained via RTI applications to the UGC and the Ministry of Education. Available at https://kuppicollective.lk/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/RTI-UGC-MOHE-reply-2023.pdf

[7] See the dissenting comments submitted by Dr. Harini Amarasuriya, MP and member of the Parliamentary Select Committee, in Volume 2 of the Parliamentary Select Committee Report (pp. 1-8)

[8] Information obtained via RTI applications to the UGC and the Ministry of Education. Available at https://kuppicollective.lk/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/RTI-UGC-MOHE-reply-2023.pdf

[9] Special Report presented by the Committee on Public Enterprises. (2021). Second Report of the Committee on Public Enterprises, Ninth Parliament, first session. Available at https://parliament.lk/uploads/comreports/1617702223080560.pdf#page=1

[10] Available at https://www.sliit.lk/course-fees/, last accessed on 14 January 2024.

[11] For a more sustained discussion of the problematic changes in State universities led by loan cycles, see the numerous articles produced by the ‘Kuppi Collective’ on this, hosted at https://kuppicollective.lk/