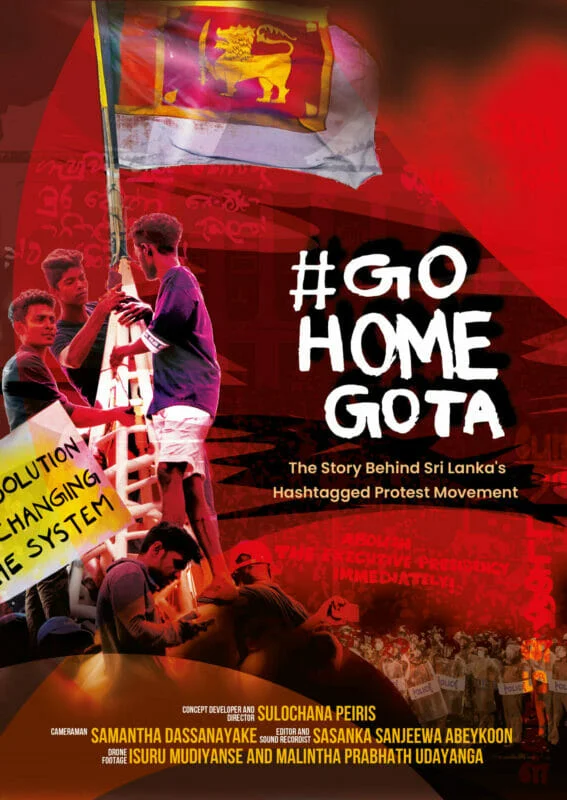

#GoHomeGota: The Story Behind Sri Lanka’s Hashtagged Protest Movement. Sulochana Peiris. 2023. 51 minutes

Oliver Walton, Deborah Johnson, and Jonathan Goodhand

#GoHomeGota is a documentary by Colombo-based freelance filmmaker and writer Sulochana Peiris that explores Sri Lanka’s 2022 Aragalaya protests. The film toured London, Coventry, Bath, Penryn, and Oxford in the autumn of 2023, when it was viewed by the reviewers.

Many of us watching #GoHomeGota during its tour in Britain had followed the Aragalaya movement internationally and had some knowledge about its context, events, and implications. Watching the documentary added wide-ranging detail but it was also powerful because of its immersive quality, which draws extensively on drone footage. The documentary is marked throughout by this dual focus: on the intimate details and personal stories, alongside a wide-angle view of a movement whose effects on Sri Lanka’s political life are still being worked out.

Early in the film the footage pans out to track a scooter winding along a road, through dense green canopy, with enormous, white letters painted along the road, “even nature hates you”. There is something in these few seconds of footage that convey a driving, forward movement whilst immersing the viewer: you can hear the engine, smell the trees, taste the trace of dust from the road.

As the focus turns to the protests themselves, drone footage gives a sense of urgency and intimacy – it reveals the scale of the protests and the way crowds move together and around Colombo landscapes, whilst offering a tangible experience of the movement.

The film also focuses on a wide range of protest art, which highlights how the movement pivoted around its ‘mimetic’ expression. Art and creativity generated an inclusive language for participation and helped to foster ‘political literacy’. The stunning white signage made up of recycled PET bottles commanding #GoHomeGota on the wire mesh of the fence opposite the Presidential Secretariat, seem as important as the crowds pulling down barricades before it.

Standing back from the film, we have come up with three questions that emerge from the Sri Lankan experience, but also perhaps point to a broader global phenomenon, in which growing numbers of people around the world feel that ‘normal’ politics and conventional development are part of the problem rather than the solution.

First, what were the origins and antecedents of the protest movement? We get fascinating hints about where the movement ‘comes from’, and what it is rooted in: political corruption, cost of living crisis, inequality, ethnic exclusion and wartime abuses, and decades of failure to democratise and reform the centralised State. These can only be hints, because each lead to questions about how far back one should go to properly contextualise and historicise the movement or its grievances. This leads to interesting comparative questions about how to read and understand the histories behind contemporary protests, including their underlying structural drivers, the triggers, accelerants and contingent events, the evolving repertoires of resistance, which are shaped by different phases and generations of protest locally, as well as experience from elsewhere.

The opening of the documentary transitions from silent monochrome pictures and words setting the context for the simmering discontent and suffering created by Sri Lanka’s escalating economic crisis before exploding into short blasts of news audio, landing the viewer with a rush into the atmosphere of the Aragalaya.

It is confusing and disorienting, but as the documentary unfolds you are guided via short interviews with movement leaders and political commentators, through the long-seated, historical causes into contemporary events. This is a movement that has been building for a decade, against a backdrop of civil war and growing authoritarianism. People in Sri Lanka have long been organising around their strengths and professions to seek justice and protect the vulnerable. The Aragalaya was not an explosion, it was the moment a simmering pot boils over, but it was nonetheless a monumental and unprecedented moment.

Peiris’ skilful narrative makes sense of this history, but it would be wrong to imbue the dynamic events with a coherent, linear trajectory. Those involved were acutely aware of the risks attached to public protest, and organisers invested huge labour into anticipating internal and external threats to the movement. The documentary shows us how those staying in the tent village of ‘GotaGoGama’ created plans for their protection, instituting village officers, legal huts, and meeting spaces. When armed thugs did eventually break into the space, seeking to dismantle the ‘struggle of love’, the message spread quickly on social media prompting thousands to arrive to protect the protesters.

Second, what were the leadership dynamics of the mobilisation, forms of protest, and official responses to these protests? This leads to questions about coalition management, mobilisation, and leadership dynamics; their strategies and tactics; the balance of societal forces and political interests aligned behind and against the protestors; how they have participated in, or responded to violence; gendered dynamics of the movement; and the ways in which ruling authorities have sought to counter protest.

One of the film’s major themes is organisation and decision making. The Aragalaya is often presented as a ‘leaderless’ movement and is described in the film as unique in the Sri Lankan context because it was a ‘voluntary mobilisation’, in contrast to earlier mobilisations in 1987 or 1953, which saw mass participation, but were led by political parties. Leaderless movements have proliferated around the world (Arab Spring, Occupy Movement, Hong Kong protests).

While a lack of identifiable leaders has helped such movements to evade government crackdowns, it has also made it difficult for them to unite around core objectives or engage with those in power. Often their effects have been ephemeral, and apparent victories short-lived. In a ‘leaderless’ environment there are still exclusions and an ongoing focus of the documentary is the importance of women to the movement as they have been to so many other intersectional struggles for justice in Sri Lanka.

The film explores these themes in depth. It demonstrates that while the mobilisation was not led by political parties or key organisations as in the past, it was nevertheless meticulously organised. The movement anticipated and reacted to violent attacks; it established complex processes for drawing up the six demands; it undertook outreach activities to mobilise people from towns and villages across the country. While the film illustrates the work of key activists and influencers through social media, it also acknowledges the important role of established groups (unions, professional associations, and political parties).

The film explores the Aragalaya’s political limitations, the ideological and political tensions within the movement, and discusses how the movement sought to manage these. One of these limitations is the fact that many in the North and East of the country see this as a ‘Southern movement’ that did not substantively address the political demands of the Tamil population linked to rights, accountability, and post-war securitisation. The documentary does not duck this issue and it is something discussed by the protagonists as well as in the commentary of human rights lawyer and activist Ambika Satkunanathan. Neither does it avoid calling out the complex balance of building on the struggles that have preceded it, often led by the most marginalised groups in society without appropriating these voices.

Digital media is a running thread through the film. The mainstream media only took interest when the movement had ‘peaked’. Instead, it was young, independent, journalists using alternative digital platforms that fostered the movement by allowing a broad range of people to participate in it, by using art and creativity to forge connections and develop their critiques of the status quo.

Third; what were the distributional effects and outcomes of different forms of protest? How has the movement shaped formal and informal politics and broader development processes? What have been the distributional consequences of their struggles? What new political subjectivities have they forged? To what extent can these movements be read as an escape from politics, or a new way of engaging with and changing politics? To what extent have governmental responses to protests changed the nature and practices of the State and democratic practices – for example in relation to human rights laws, policing, and surveillance?

The film does not shy away from the reality that although millions were mobilised around the goal to remove President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, a movement capable of transforming the status quo around coherent and inclusive goals has remained elusive. The film explores the role of women in leading protests (both in Colombo and in Batticaloa), as well as efforts to acknowledge wartime atrocities through a Mullivaikal remembrance event. It also reflects on divisions between different factions: Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna supporters, liberals, and those supportive of people’s councils.

The reversals since Gotabaya’s resignation have led many to question the longer-term impact of the Aragalaya. The film explores some of its more intangible consequences – carving out an independent space for peoples’ activism, changing expectations about protest and citizenship (particularly the emergence of public protest as a respectable space beyond ‘rabble rousing’), and helping to foster new political subjectivities which may have a greater chance of enduring despite efforts by political parties to co-opt the Aragalaya’s agenda, or government crackdowns. The film includes some critical reflections that stem from this on the meaning and challenges associated with ‘system change’, questioning whether political reform will be sufficient without wider social change.

Despite providing sustained reflection on the movement’s tensions and limitations, the film’s greatest strength is perhaps that it does so without detracting from the optimism and energy of the protests and the possibilities for systemic change contained within it.

Oliver Walton is a Senior Lecturer in International Development at the University of Bath. Deborah Johnson is a Senior Lecturer in Politics and International Relations at the University of Exeter. Jonathan Goodhand is a Professor in Conflict and Development Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.