Claiming Identity, Dignity, and Justice: Malaiyaha Tamils of Sri Lanka

B. Skanthakumar

The 150th anniversary of the beginning of the tea industry in British Ceylon was marked in 2017 by a range of government and corporate events, mostly to promote Sri Lanka’s premier agricultural export. In counterpoint, the Gampola-based Tea Plantation Workers Museum and Archive hosted a symposium in Hatton that year, with the purpose of redirecting attention from crop and product, to cultivator and producer.

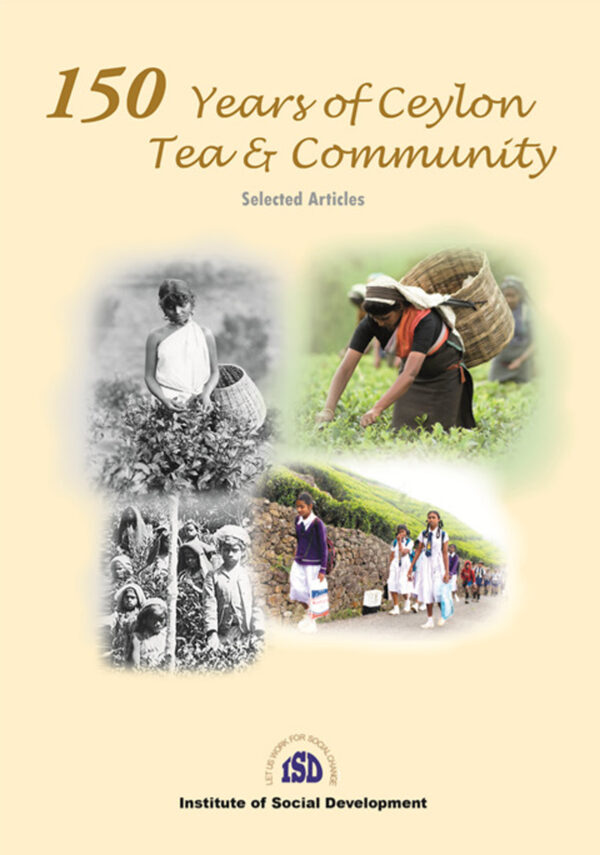

Five papers: on historical dispossession; variations in production models; social and political exclusion in the North and East; women’s participation in unions and parties; and plantation political patterns, were subsequently published as ‘150 Years of Ceylon Tea and Community’ by the Kandy-based Institute of Social Development.

Historical Context

Emeritus professor at the University of Madras, V. Suryanarayan’s keynote conference paper, from which the title of this review is borrowed, opens the volume. He begins with the conditions in which those trapped in chronic indebtedness to landowners and rural moneylenders in southernmost India were forced through hunger and destitution to migrate across the Palk Straits for food and waged work.

Those who survived poor health, disease, and danger to reach the forested interior, cleared land for coffee and later tea and rubber cultivation; planted and plucked or tapped; and constructed road and track for conveyance of commodities from source to Colombo and beyond.

In a “bird’s eye view of the problems and prospects of the Hill Country Tamils from an Indian perspective”, the poor educational level of the community and the lingering legacy of decitizenisation and disenfranchisement post-independence, are highlighted as particular concerns.

Suryanarayan decries the longstanding disinterest of Northern and Eastern origin Tamil leaders, related by language and culture but estranged by caste and class, from taking up the cause of another group of Tamils. The politicians of Tamil Nadu are no better in his opinion for having failed to integrate stateless persons repatriated, whether by choice or coercion, under the terms of official agreements between India and Ceylon/Sri Lanka: the Sirima-Shastri Pact of 1964 and Sirima-Gandhi Pact of 1974; and those displaced by violence and conflict after the July 1983 pogrom and since resident in South India.

To lift the educational standard of the community and better the future of its youth, a free mid-day meal and bus pass for children in plantation districts, and hostel facilities in major towns, is proposed. As a disadvantaged community, the government could assist Hill Country Tamils through reserved admission to schools and higher education institutions, as well as access to scholarships and employment, he recommends.

Changing Plantations and People

Professor A. S. Chandrabose of the Open University of Sri Lanka situates the evolution of the plantation community within Sri Lankan society, in the changes in the tea plantations from nationalisation in the early 1970s to privatisation in the early 1990s. Through this transformation, he explains how a community once bonded to the estate and relatively immovable, has been rendered mobile in the reserve army of labour.

He notes how while nationalisation was deemed a failure owing to low productivity and high production costs compounded by political interference and mismanagement; post-privatisation, the Regional Plantation Companies have performed poorly in harvesting of tea leaf, acreage under cultivation, and replanting of aged bushes, particularly in comparison with smallholdings which now account for over 70%of production.

According to Chandrabose, companies have pushed down the cost of production through reducing the number of registered workers; reneging on the 300 days of work guaranteed by collective agreements; and re-employing retired workers as temporary or casual labour without social security entitlements.

He proceeds to outline the latest production model for the plantations, which is the ‘out-growing’ or ‘revenue-sharing’ system promoted by the Planters Association of Ceylon. In a hybrid system, workers are to be offered a fixed number of days of waged work each month based on the current plucking norm; and remunerated on other days on a per kilo rate.

In this labour regime, the cost and risks of cultivation are exclusively borne by the out-grower, who is obliged to purchase inputs from, and sell the green leaf exclusively to, the Regional Plantation Company (rather than on the open market). The land remains under leasehold to the company and the bushes under its control.

What incentive then for today’s waged worker to become tomorrow’s contract farmer? Based on the smallholder sector, where the number of kilos harvested is considerably higher than the current norm in the plantations, an increase in the yield and consequently daily income is assumed to follow.

The self-exploitation of the plantation household (as family labour is inevitably applied to increase the yield from the allotted bushes) – in the absence of any transfer of land or even security of tenure – is apparently their pathway out of poverty and coolie status.

Chandrabose is aware of several problems with the current out-grower system in Sri Lanka. The assigned tea bushes are invariably aged and therefore low yielding. The number of bushes allocated is too few, and the length of the informal agreement too brief, for durable gains for the producer. Housing on the estate is tied to at least one member of the household remaining in waged work for the company. In times of illness, injury, and infirmity, the responsibility of social protection shifts from the company to the household and the State.

Caste and Culture

The second part of his paper argues that the ‘repatriation’ of dominant castes in the 1960s and 1970s created a vacuum in leadership on the estates; and the decline if not demise of unique cultural traditions of the plantation community in Sri Lanka, of which they were the main practitioners.

Not here but elsewhere[i], Chandrabose has identified some of these castes as Mottai Vellalar, Reddiyar, Agamudaiyar; Ambalakarar; Kallar; Naidu; Mudaliyar; Padayachi; Udaiyar; Gounder, and more. He contends that they contributed to the travel of the agrarian festivals and folk drama, dance, and music from the hot plains of the Madras Presidency – for example, Kaman Koothu; Ponnar Sangar; Archunan Thapasu; and Margali Bhajan – and their translation in the cool hills of the former Kandyan Kingdom.

It took until the mid-1990s for a generation of educated youth to provide renewed community-based leadership. By this time ‘Sinhalese culture’, by which he means the language, dress, and forms of worship of the majority community, had permeated the plantation community. Unsurprisingly where Hill Country Tamils are a dispersed minority (for instance Galle, Matara and Monaragala), this extended to the assimilation into Sinhala society of some, amidst racist attacks, compounded by decades of an ethnicised internal war.

Absent in this narrative though are the shifting fortunes of kanganies (labour recruiters and field supervisors) and branch union leaders (thailavars) as elites among estate Tamils; and how the cinema, film music, and television, of Madras/Chennai shape and reshape culture and identity, past and present, on the plantations.

North and East

Hill Country Tamil migration to urbanised Sinhala majority areas in the West and South-West of the island is a perceptible trend. What is less known is that decades before, some Hill Country Tamils moved to rural Tamil majority areas in the North and East seeking physical security, land to farm, and the promise of a better life.

The internal migration of Hill Country Tamils, and their experience of social and political exclusion by their co-ethnics, resulted in their formation within the North and East as a distinct sub-category within Sri Lanka’s Tamil community, contends P. Muthulingam, Executive Director of the Institute of Social Development.

Beginning with discriminatory legislation in the late 1940s and the rise of majoritarianism including the ‘Sinhala Only’ language Act in 1956; following the anti-Tamil riots of 1958, Hill Country Tamils in Galle, Kalutara, Monaragala and even Badulla and Nuwara Eliya were pushed to move to the Vanni and to Pullumalai in Batticaloa district within the Tamil-speaking North and East.

Even along the Vavuniya-Killinochchi (A9) and Badulla-Chenkalady (A5) roads respectively, these were sparsely populated, forested areas, with poor infrastructure and facilities, and undesirable to locals. Their numbers were swelled by successive anti-Tamil violence: in 1963 (in Bandarawela); forced eviction following land reform and starvation deaths between 1972 and 1975; and riots in 1977, 1981 and 1983.

Meanwhile through the 1970s there was a pull from North-Eastern Tamil activists to populate the border zones of the North and East, as a counterweight to the State-sponsored settlement of landless Sinhala villagers, in what the former considered to be their ‘traditional homeland’.

The non-governmental Gandhiyam organisation developed large model farms in the Vanni where thousands of displaced Hill Country Tamils resettled. Left wing armed militant youth organisations – the Peoples Liberation Organisation of Tamil Eelam, the Eelam Peoples’ Revolutionary Liberation Front, and the Eelam Revolutionary Organisation of Students – adopted the cause of Hill Country Tamils, established villages for, and enlisted, them. By the late 1980s, these organisations were decimated by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam; which voluntarily and through conscription in the areas under its control, would recruit up to 12,000 Hill Country Tamil origin youth as cannon fodder, peaking in the war’s endgame in 2008-2009.

The early settlements were largely a failure. Subsistence farming was unfamiliar, and income was poor. Their only asset was the land adjacent to the main roads, which once cleared for cultivation and with rising value was soon attractive to locals, pushing the migrants into the poorly irrigated interior, and for work as agricultural labourers or chena cultivators.

Through 80 oral interviews, 10 community discussions, and ethnographic observation, Muthulingam has recorded the origins and evolution of surviving Hill Country Tamil new villages (styled by landowners as purams or nagars) spanning Mannar, Killinochchi, and Mullaithivu across the North through to Trincomalee and Batticaloa in the East. These names are also markers of origin, caste, and identity of their inhabitants and for “exclusions in social development, access to governance structures, land ownership, and other welfare rights”.

The spur for the post-war political mobilisation of Hill Country Tamils appears to be the discrimination in provision of rural roads, water to drink and for agriculture, and income generation projects against the new villages, and in favour of the older ones inhabited by locals, by government officers and political representatives of Northern and Eastern Tamil origin. An important memorandum on their grievances on livelihood, housing, education, political representation, employment, and infrastructure development, prepared by the ‘Malaiyaha Makkal Forum of the Northern Province’ in 2017 is annexed in this volume.

In the remainder of this chapter, Muthulingam describes struggles for political representation of this community within a community in the Vanni. The 2011 local government election was a breakthrough as Hill Country Tamils were elected in Killinochchi and Vavuniya through the Tamil National Alliance, Eelam Peoples Democratic Party, United National Party, and United Peoples Freedom Alliance. Nevertheless, the community remains under-represented in local bodies and unrepresented in provincial institutions. Drawing a parallel with the condition of the ‘repatriates’ in South India, he cautions that their integration as equals into the Tamil community of the North and East is not only unrealised but also uncertain.

Hill Country Tamil Women

Development practitioner T. Kalaimagal seeks to evaluate the place of, and emerging new avenues for, Hill Country Tamil women in trade unions and politics. In a sector where women predominate in the labour force, their under or token representation in leadership bodies of trade unions, their absence from collective bargaining and other decision-making discussions, and the gender blindness if not male bias of trade union programmes, seriously undermine the representativeness, legitimacy, and relevance of traditional workers’ organisations.

This is not to say that women have never benefited from trade union membership or action. Equal pay for women plantation workers was a demand and victory of combined plantation trade union strike action in 1984. Meanwhile Collective Agreement No. 13 of 2003, negotiated by trade unions, has provisions of concern to women workers: on transport to hospital, maternity leave, funeral expenses, and crèche facilities.

Kalaimagal notes that the women’s committees (mathar sangam) in trade unions have not empowered women members nor advanced women’s agendas within trade unions. On political parties, she cites researcher Chulani Kodikara who found that women’s wings of political parties in Sri Lanka exist to mobilise women during elections – for the purpose of voting men to power – and for social service activities in between.

In her only primary data, she interviews Saraswathi Sivaguru who leads the Women’s Wing of the National Union of Workers, and was the first Hill Country Tamil woman elected to the Central Provincial Council (2013-2018). Sivaguru makes reference to the pressure on women leaders to “conform to the male leadership model”. Structural, organisational, and procedural changes within trade unions are required for women’s inclusion and leadership, says Sivaguru. The introduction of a quota for women’s participation and representation in the 2018 local government elections is hopeful, according to her.

Political Patterns

Ramasamy Ramesh of the Department of Political Science in the University of Peradeniya “endeavours to discuss the emerging political patterns, changing political aspirations, the status of the traditional political leadership and the role of upcountry political parties in the State reforms process in Sri Lanka” in the concluding chapter.

He observes that whereas in general in Sri Lanka, trade unions were floated by political parties, the reverse is true of the plantations. The Ceylon Workers Congress, the Democratic Workers Congress, the Up-Country Peoples Front, and the National Union of Workers, have had a dual role in the plantations beginning as trade unions and developing into political parties.

Over time and accelerated by the restoration of citizenship rights to stateless Hill Country Tamils and therefore their enrolment as voters, party politics has taken precedence over union politics. These parties are personality driven; and least interested in “political ideologies, policies, party organisation, democratic values in party organisation, and decision-making”. The traditional leadership practised issue-based politics based on coalition-making with the governing party at the centre.

“With the resolution of [the] citizenship issue” argues Ramesh, “institutional discrimination, inequality in governance structures, developmental rights and public service delivery became a matter of serious concern among upcountry political leaders, especially among [the] emerging new leadership”.

The popularisation of the concepts of Malaiyaham (hill country) as home, and Malaiyaha Thamilar as identity (in place of ‘Indian-Origin Tamils’) by the Up-Country Peoples Front during the 1990s, is crucial to this new consciousness.

This new leadership also aligned with Sinhala majority political parties, has engaged in State reform of the political and governance institutions to address the “incomplete citizenship” of Hill Country Tamils. Their composition includes educated youth, civil society activists, progressive academics, and intellectuals, churned out by class differentiation within their community, and critical of the Ceylon Workers Congress, which has long dominated the trade union and political landscape of the plantations.

In the past, the political parties of the plantations have been muted on national issues such as corruption, development policy, and state reform, focusing only on an ethnic minority issue-based agenda. Significantly, the Hill Country Tamil community demonstrate a more progressive understanding of politics than their traditional leadership, believes Ramesh. They favour political pluralism by supporting diverse political parties. They wish to weigh in on national controversies and debates. They want to be in the social and political mainstream.

Drawing on political scientist Jayadeva Uyangoda and sociologist Laksiri Jayasuriya, Ramesh points to the difficulties of achieving social rights in this period “when fully fledged welfare policies and programmes started withering away and neo liberal economic and social policies came into force…”. This dilemma is side-stepped by the plantation leadership who look to the regime in power, donor agencies and non-governmental organisations, to meet the needs of the people.

As legal citizenship (symbolised by the 2003 Citizenship Act) has not over-turned the inequalities and discrimination experienced by Hill Country Tamils, he invokes Canadian philosopher Will Kymlicka to press for differentiated citizenship rights: unique policies and programmes that recognise the claims of ethnic and other minorities and overcome their marginalisation.

Overall, this publication will be of interest to anyone interested in the continuing journey of the tea worker from chattel to citizen. It advances contemporary claims for identity, dignity, and justice; acknowledging the challenges and contradictions along the way. The book has its limitations and unevenness, particularly in the treatment of gender relations and women’s subordination. The view from Kegalle and Ratnapura, not to mention Matara and Monaragala, may differ from the high-grown districts.

The Malaiyaha Thamilars have come far. But their long trek within Sri Lanka is far from over.

B.Skanthakumar is co-editor (with Daniel Bass) of Upcountry Tamils: Charting A New Future in Sri Lanka (International Centre for Ethnic Studies, Colombo 2019).

Image Credit: https://bit.ly/3s1zuwY

Notes

[i] Chandrabose, A. S. (2014). ‘Cultural Identity of Indian Tamils in Sri Lanka: A Measurement of Multi-dimensional Status of the Indian Tamil Society in Sri Lanka’. In Garg, Sanjay (ed.), Circulation of Cultures and Culture of Circulation: Diasporic Cultures of South Asia During 18th to 20th Centuries. Colombo: SAARC Cultural Centre, Sri Lanka. Available at http://saarcculture.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/diasporic_cultures_A_S_Chandrabose.pdf.