Sri Lanka 2023: Anniversaries of Struggle

Q. M. Saul

No matter what happens for the rest of this year, 2023 will go down in the history books of Sri Lanka. This year is like one of those astronomical alignments which only come around once every few centuries. Not only does the country face unprecedented crises this year; it also commemorates the combined anniversaries of major events that have defined modern Sri Lanka. Through the lenses of these anniversaries, the countdown of this year’s challenges come into fresh focus. They will come according to our doing.

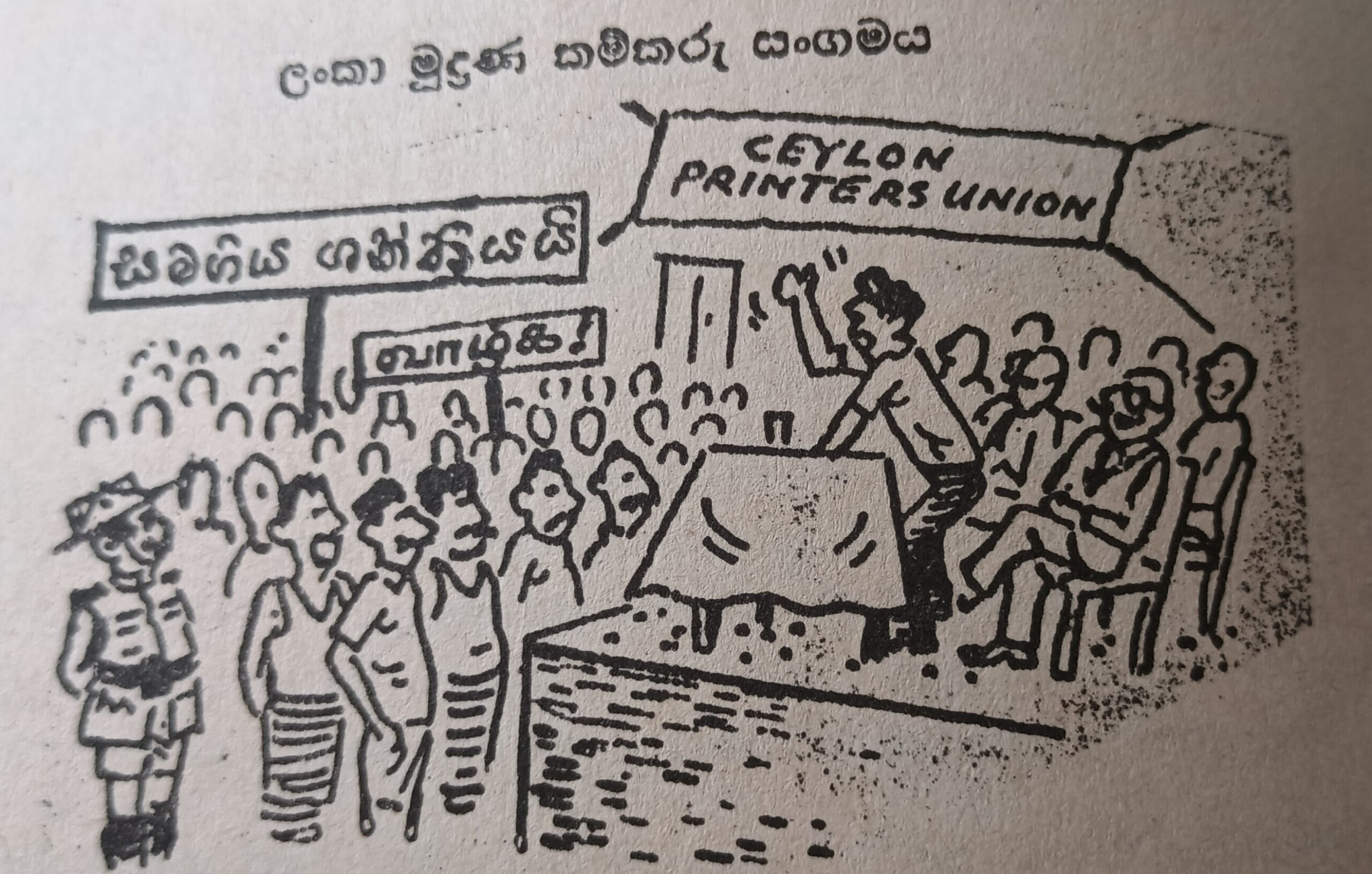

1893: 130 years ago, the first strike was called and the first trade union formed. The Ceylon Printers Union formed to bargain collectively with H.W. Cave and Co; it led 60 workers on strike because they hadn’t been paid on time. 400 joined the union which included Sinhalese, Tamil, and Burgher workers. The union’s leadership was fired and after six days the strike was broken – the battle was lost but the class war had only just begun. The printers fired “the first salvos in shattering the industrial peace of colonial Sri Lanka” (Kumari Jayawardena).

1923: 100 years ago, 20,000 workers joined forces in the first general strike in Sri Lankan history. Led by the Ceylon Labour Union and affiliated to the Ceylon National Congress, this was a turning point in history. What began in a small print shop had culminated in island-wide economic power, and pointed towards politics.

1933: 90 years ago, a major strike at Wellawatte Mills went on for two months. When the Ceylon Labour Union refused to support these workers, and even joined with employers to bring in strike-breakers and divide the workers on ethnic lines – they turned to the Left. This strike signalled the emergence of anti-capitalist leadership in the labour movement. The same year, the Suriyamal Movement was launched; an island-wide mobilisation led by women which would lay foundations for Independence. These movements grew together – large assemblies of women wearing red became a signature feature of every trade union action in this period.

1953: 70 years ago: a country-wide decentralised movement of civil disobedience, sabotage and satyagraha erupted, known as the Hartal. Provoked by steeply rising prices of rice, transport and new taxes, people were restless. Finance minister J.R. Jayawardena advised the poor to grow their own food and gave tax concessions to the rich. Left leaders called for Hartal; and the power of the people was unleashed like never before or since. Roads were blocked and bridges blown up. Trains were held hostage; tracks torn up; telegraph lines torn down. Women faced down police batons with kithul clubs. Black flags flew from Colombo to Jaffna. An anonymous policeman’s testimony tells all: “We are only six thousand; what can we do against eighty lakhs?” The police and army fired live ammunition but crowds didn’t disperse; they held their ground and sometimes fought back. The government leadership hid on a British warship in the Colombo harbour; they were right to be afraid. (Only a few weeks before Fidel Castro had attacked the Moncada barracks in Cuba; a general strike was sweeping France; and communist China’s first five-year plan had just begun.) In Sri Lanka a united urban and rural working class had seized the commanding heights of the neo-colonial export economy – transport and communications. Afraid of what they had started, the Left leadership called the Hartal off; hundreds of arrests began.

1963: 60 years ago, and ten years after the Hartal, the Sri Lankan working class reached the highest state of unity and organisation to date. In April, recognising that isolated strikes had been unsuccessful, the Ceylon Trade Union Federation convened the first conference of all unions. The Joint Committee of Trade Unions represented workers in every sector of the economy; private and public, clerical and manual, rural and urban. On May Day of that year there was a gigantic demonstration on Galle Face Green, the likes of which had never been seen before. In September, 800 delegates representing one million workers met and formulated 21 demands. A seventeen-day strike at the Colombo harbour brought the point home. Its leaders were invited to join the government.

How will these epic anniversaries be commemorated? Remembered with nostalgia? Forgotten with shame? Exorcised with fear? Celebrated with struggle? For context, President Ranil Wickremesinghe has argued that the scale of the crisis facing Sri Lanka today has not been seen since the collapse of the Rajarata Civilisation. This diagnosis and his prescriptions were articulated in the early days of his presidency and his counsel is clear: a shock doctrine of neoliberal reforms courtesy of international finance capital. What’s less clear is the position of the mass movement which unwittingly brought him to power.

Not just Sri Lanka but the whole world is in a crisis of civilisation. And almost everyone from the farms of India to the industries of France, seems to agree on struggle. “Aragalaya” has unique Sri Lankan characteristics but most countries in the world are facing major economic crisis and popular unrest. With struggles behind and struggles ahead, this year of alignments is a window of opportunity to reflect on what it all means.

Quincy M. Saul is a writer and musician, organiser of Ecosocialist Horizons, and an editor of the journal Capitalism Nature Socialism.