Relevance of an Alternative Film-Culture Today

Laleen Jayamanne

Thank you for inviting me to speak on Dharmasena Pathiraja’s fourth death anniversary, on the ‘Relevance of an Alternative Film-Culture Today’, the topic suggested to me by the organisers.

My talk has two parts. In the first, I’d like to share with you a couple of thoughts that I have been reflecting on for some time about Pathiraja’s legacy for us today as a mentor. The name ‘Mentor’ comes from Homer. He was the guardian of Osysseus’ son during the father’s long absence at the Trojan war. So, a mentor is a special kind of teacher who cares also about the ethical well-being of the student. In the second part, I will briefly map out the history of the struggles that went into creating the new idea of ‘film-culture’ in Europe, taking two key examples from two silent films and a third example from contemporary indigenous film culture in Australia.

Part 1: Pathi as Mentor

- At the official government celebration honouring 50 years of Pathiraja’s work in the Lankan film industry, attended by then President Maithreepala Sirisena, Pathi gave a short and uncompromisingly powerful speech. Speech is hardly the word because Pathi’s voice was, as always, so soft and quiet, but its ethical force was remarkable, even exemplary. He said, “I have never celebrated my birthday or any anniversary for that matter.” He appeared to be ill at ease with the pomp of the ceremony leading him on with Kandyan dancers and drummers. He jokingly undercut the idea that he had worked professionally in the Lankan film industry. He asked, rhetorically, “What industry? How can there be an industry without capital, if there is no professional stability and proper infrastructure? When we look at the sad last days of Rukmani Devi, Dommie Jayawardena, and Eddie Jayamanne, how can we speak of an industry? I wasn’t a filmmaker professionally. Was anyone able to make a living professionally? I made a living by teaching as a lecturer from 1968-2008” (Maha lokuwata, arambaye sita karmanthayak gana katha keruwath, ape athdakeema anuwa wurthiya sthawarathwayk nathnam kohomada karmanthayak thienne!). He claimed that the people who say there is an industry are the exhibitors and some producers, and that the state must support the new generations of young filmmakers who are yearning to make worthwhile films. With his friend former President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga also present, he admonished the President to control and punish those groups of jatalayan[i] and nigantayan[ii], who under the cover of the robes, were engaged in violence. While leaving the renewal of the Buddha sasanaya to ethical Buddhist monks, he stated that a secular state must be established in Sri Lanka. This is Pathi as a fearless public intellectual, speaking Truth to Power.

- The second thought came to me when I read on the internet, the valedictory epistle to Pathi written after his untimely death, by Professor of English, Sumathy Sivamohan. Sumathy indicated that he was a mentor to her in an unofficial apprenticeship as a filmmaker. I note here the absence of a skills training programme in the country, despite being recommended by the 1965 Commission of Inquiry into the Film Industry in Ceylon, chaired by Regi Siriwardena. Pathi encouraged Sumathy to develop her confidence and thereby her skills by observing how others worked. He demystified the process, which has not been traditionally accessible to women. They educated themselves on film history, both Indian and other, they “argued like hell”, she said. This apprenticeship matters, I think, because Sumathy in her four films so far has created a small but significant body of work centred on inter-ethnic relations and experiences of dispossession suffered by minority communities: on Malaiyaha Tamils/Estate Tamils (the minority Tamil community brought over from India by the British as indentured labour to work in the coffee/tea plantations) especially their women, in Ingirinthu (2013), and of the mass expulsion of the Muslim populations of Jaffna and the Mannar area by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) during the civil war in A Single Tumbler (2020). Amid the Villus: The Story of Palaikuli (2021) is a documentary on the difficult repatriation of some of these very Muslims.

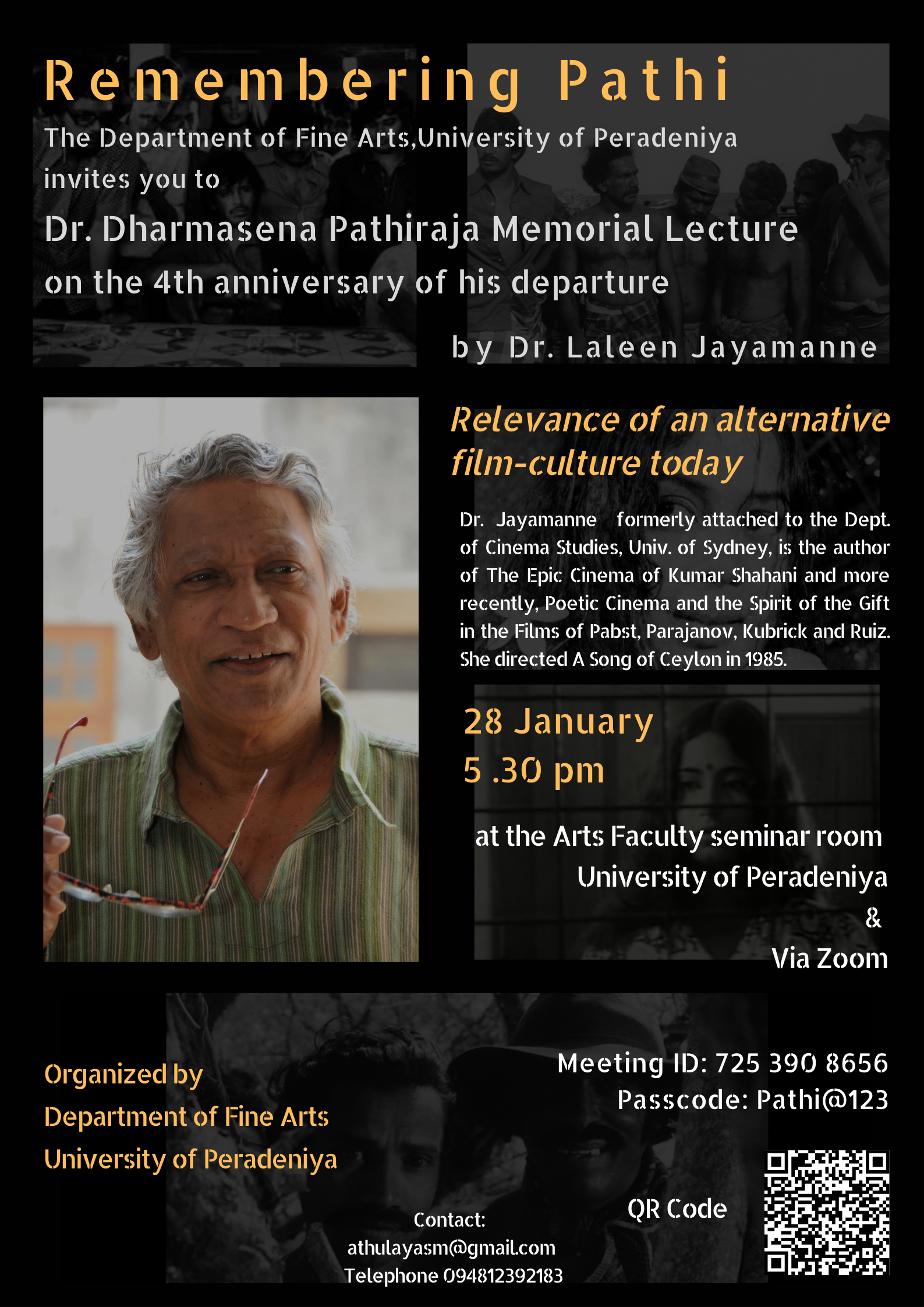

Still image from Sons and Fathers.

Her film Sons and Fathers (Puthu saha Piyavaru) (2017), in Sinhala, focuses on the multi-ethnic composition and inter-marriage among people, including a musician who worked in the Sinhala film industry from its early days. It is probably the only film about the Lankan film industry. In one searing sequence it shows an elderly man being violently dragged out of a building during the ’83 pogrom (against the Tamils) and then a long shot of a burning car, of the same model in which the film producer K. Venkat was burned alive. The film crew knew his car and even his number plate and filming this was of vital importance to all of them. The film bears witness to the burning down of Tamil-owned film studios, including Vijaya Studios owned by the great pioneer K. Gunaratnam, who produced the box office success Sandeshaya (1960), by Lester Peiris, after Rekava flopped; a fork in Lester’s career path and that of the industry too. The Sinhala nationalist mobs did not care that they were destroying their very own film infrastructure, films and film culture, ignorant of the pioneering role Lankan and Indian Tamils have played in the establishment of the fragile Lankan film industry, in its three tiers of production, distribution, and exhibition. Sumathy also collaborated with Pathi on several film projects—writing scripts for him, notably In Search of a Road (2007), made during the civil war. She has done several activist films, one of which is called A Child Soldier. I think she is perhaps Sri Lanka’s sole woman filmmaker who has made its fraught, bloodied, multiracial history her area of on-going film research, within a critical understanding of the larger historical forces determined by both the Sinhala nationalist state and the Tamil nationalism of the LTTE, during the civil war era and in its aftermath.

Funeral Procession, Ponmani.

Pathi began his own cross-cultural exchange by making Ponmani in 1977 with his friends and colleagues whom he met while lecturing at the Jaffna University. We should be thankful to the University administrators for their foresight in sending Pathi to the Jaffna campus to plant the hybrid seeds of a film culture. It turned out to be a most productive and joyous period for Pathi in forging durable links with both Tamil scholars and artists. I like to think that, perhaps, in its own oblique way, the collaborative nature of Ponmani may have prepared fertile ground for the creation, war-ravaged decades later, of the ambitious Jaffna International Film Festival, a robust alternative film culture institution, bypassing Colombo, but also the dead end of Sinhala parochialism. In this connection the steadfast work of Anoma Rajakaruna should be mentioned.

In each of their films Ponmani and Puthu saha Piyavaru, Pathi and Sumathy have crossed into cultural and ethno-linguistic territories that are outside their own familiar social experience and mother tongue. But there is not a single shot in these films that can be termed ‘picturesque’. The idea of the picturesque was developed in 18th century Britain to describe a ‘picture perfect’ image of landscape for painting and was part of the Romantic aesthetic. It was a middle path or term between the much more complex aesthetics of the ‘Beautiful’ on the one hand, and on the other, the aesthetics of the ‘Sublime’, proposed by Edmund Burke. The picturesque petrifies actual space into a pleasing image. There is an easy slide from landscape pretty-fied in this way to how women are presented as ‘picture perfect’, like the Kodak moment of the 20th century celluloid past. I bring up this critical point here because I see every now and then a tendency to present images of Jaffna landscapes and also Tamil women, in a picturesque manner, which is linked, I think, to the film festival circuits essential to the life of independent film. Film festivals themselves, historically European, were alternative film-culture institutions created to bypass the control of global exhibition and distribution by Hollywood Studios. The picturesque images are familiar clichés of European art cinema, a lingua franca of sorts of the ‘festival film’, as it is sometimes referred to pejoratively. This seemingly harmless aesthetic only becomes an ethical and political problem when the territory or the body filmed is riven with violence, because it converts that very violence into a pleasing/picturesque image to be consumed.

The familiar tourist aesthetic of the picturesque camera shot, (as in some images in Funny Boy by Deepa Mehta, pointed out by Boopathy Nalin), is a continuation of this Romantic, ahistorical aesthetic. To understand an entirely different approach to an unfamiliar phenomenon or culture, see how Sumathy films the donkeys foraging in garbage on a busy roadside in A Single Tumbler. She has said how they fascinated her when she first went to Mannar, also known as ‘Donkey Town’. These donkeys were first brought to Lanka about 1000 years ago by Arab traders and grew feral when the Muslim people, who used them as domesticated work-animals, were expelled from Mannar. They now cause traffic hazards and get seriously injured, so a donkey hospital has been created to tend to them, which has in turn become an eco-tourist attraction for animal lovers. So, the donkeys in Sumathy’s film function as a rich neorealist ‘fact-image’ as theorised by Andre Bazin, the great French film critic. The donkeys carry a historical load, and are not used picturesquely to evoke pathos, which is so easy to do with a donkey, especially on film. (Think of Robert Bresson’s film about a donkey named Balthazar).

In fact, as a scholar of Lankan cinema, it’s my opinion that an alternative narrative of Lankan film history will need to be conceptualised to take account of Sumathy’s film project. The question of whether you like her films or not, is really irrelevant to the necessary and principled acknowledgement of a body of work developed with a rigour and consistency, now for over a decade. With her work, the Lankan film history cannot simply be thought of as one of inevitable, natural, linear generational change among its rather rare and therefore important, gifted, and brave male filmmakers, beginning in fact with Pathiraja himself in Ahasgauwa in 1974. Both Pathi and I shared our reservations about the rather glib generational narrative of the ‘Sinhala cinemave vansa kathava’. As we know, history is not natural, nor is history inevitable; there are paths not taken which might have averted tragedy.

Part 2: The idea of a Film-Culture – a historical sketch

I thought it might be useful to provide a historical perspective, to outline why and how European cinephiles and filmmakers struggled to realise the idea of a Film-Culture in the early 1920’s during the silent cinema era. Specifically, I will discuss the Soviet political avant-garde and the French Impressionist avant-garde cinema and two or three ideas and concepts they formulated, still vital for thinking about film and indeed making films. In addition, I will briefly outline our own, vibrant contemporary First Nations’ alternative film culture in Australia.

But first, some elaboration of the terms in the title which can’t be taken for granted. The notion of an ‘alternative’ obviously implies something that is posited as given (for example, the commercial industrial cinema, or a cinema promoted by an authoritarian State). So there is a sense of an opposition to something, or a marked difference built into the term ‘alternative’.

The two words ‘Film’ and ‘Culture’ were conjoined with difficulty, at first, in Europe. The etymology of the word ‘culture’ has links to agriculture and the idea of cultivation of crops. It’s a process of growth—an activity. The very combination of these two terms has a long history. Historically, the word ‘culture’ was never neutral in Europe. High-Culture, as you know, was especially powerful in Europe linked to social class, inherited wealth, and privilege with access to vast bodies of knowledge over centuries. A great deal of the art of Europe was created for royalty and the church and, after the French revolution, for the bourgeoisie with access to learning and cultivation of taste. The term ‘culture’, or to ‘be cultured’, meant sophistication in matters of taste, connoisseurship, and implied that there was a class that was not cultured. There was what was thought of as a low-culture or a popular culture of the people for which literacy was not essential.

The word ‘culture’ in Britain was subjected to deep scrutiny by the Marxist scholar Raymond Williams, a founder of Cultural Studies. He widened our understanding of what ‘culture’ meant. He showed us how it was much wider than what the upper classes considered to be high culture. It was also something more than what colonial anthropology studied as culture, when they did ethnographic research into so-called primitive oral cultures and their practices, often in Africa and Australia, in the colonial world. Williams, coming from a working-class Welsh mining background, and going on to Cambridge University, pioneered the long process of democratising the word itself, as a conceptual tool. He opened the way for the study of many aspects of human, every-day activity in modernity, that were not captured by the previous ways of defining culture. His books Culture and Society (1958) and Key Words (1976) are foundational texts in cultural studies, and now there is a more recent iteration of the latter, New Keywords: A Revised Vocabulary of Culture and Society (2005) edited by Tony Bennett, Lawrence Grossberg and Meaghan Morris.

In South Asia, take the word ‘Sanskrit’. As you know well, it is the name of a classical Indian language, with a vast body of writing in many spheres of knowledge in philosophy, aesthetics included. In Sinhala it is also the word for culture, with a small modification of the word—Sanskrutha-Sankruthiya. The former as you know is the language and the latter is the word for culture. Culture here presupposes the ability to read and write Sanskrit, which was the privilege of the Brahmin caste in India. So, it is exclusive. The rest spoke Prakrit, the vernacular languages of the people, like Pali in the time of the Buddha, an oral language. Can you say in Sinhala, ‘chitrapata, or cinema-sanskrutiya’ in the way we can easily say ‘film-culture’ now? If so when did that become possible? Was it possible before Rekava, say? Can we speak of cinema and civilisation in Sinhala? Civilisation being an achieved state, a heritage. Cinemawa and Shishtacharaya? You will know better than me. I think it’s probably easier to say cinemawa saha nuthanathwaya (cinema and modernity) and make sense of it as a modern technology offering new sensations, perceptions, and feelings. My 2014 book on the epic cinema of Kumar Shahani argued that he, Ghatak, and Mani Kaul, have brought film into an intimate engagement with Indian civilisational arts such as music, dance, sculpture, architecture, and textiles. But their history is different from ours: more diverse, syncretic, and arguably therefore richer in complexity.

The opposition between ‘Film’ and ‘Culture’ was very stark at the beginning of the history of cinema from 1895 onwards in the West. This was because film was first and foremost a product of the industrial revolution, a mechanical process that registered images, not handmade as art was traditionally, and it was a commodity bought and sold by the yard, at first. The very first audiences for these short films were urban working classes and immigrants as in the case of US audiences in big industrial cities, many of whom did not speak English and were illiterate. But they were able to follow the images as they developed ways of telling stories visually. The early working-class audience and the cheap popular venues in slum areas where film was first shown, gave film a very bad reputation because the first audiences were illiterate workers, including sex workers and others thought to be socially undesirable types. Puritan church groups and social reformers were particularly opposed to film, as it created an unregulated illicit public sphere encouraging what they considered immoral behaviour. Film most certainly was not where Culture was. It was considered by some as a culture-destroying force in Germany. Now as film itself developed a market, its previously low status began to change fairly fast. A middle-class audience came to see film, once legitimate theatre and novels were used as the basis for film narratives. By 1915 the class base for cinema had widened. Film acquired social prestige. The US, without an inherited high culture like Europe, was able to develop film as a robust popular mass culture, giving US cinema a unique place also linked to its growing economic and political strength, and the consequent cornering of global markets after World War I. Ideologues of US cinema called it ‘Democracy’s Theatre’, ‘The Universal Language’, etc. For them, film’s primary social function was entertainment, which generated great profit. Hollywood fashions stimulated trade. Woodrow Wilson, the US President, once said that for them trade always follows the pictures.

In contrast, in the Soviet Union, Lenin famously said that film was the most important of the arts for them, because the majority of people were illiterate but could understand Soviet history through images. So, for them film was a powerful means of education of the illiterate masses which was placed under the Ministry of Education. In France in the 1920s critics and film directors like Ricciotto Canudo and Jean Epstein emerged, who were convinced that film technology was a unique modern medium and went about exploring its original properties and began to develop the idea that it was in fact the seventh Art, the other six being painting, architecture, sculpture, music, dance, and theatre. In this way, through a discourse of art, film was legitimated in France and valued as such. This is the beginning of the idea of an art cinema.

In fact the first generation of European filmmakers and theorists, Sergei Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov, Jean Epstein, Bela Balazs, all born in the late 19th century, grew to maturity during the horrors of World War I which was conducted with the most advanced weapons of mass destruction. Therefore, they felt an urgency to speculate on the new mass medium of cinema to see how it could offer a more humane vision of life in modernity rather than mass death. They saw in the camera eye a unique instrument for seeing the world anew, and the new film techniques as a way of reshaping the experience and consciousness of the masses. Cinema as a true art for the masses offered modernity’s ‘promise of happiness’ so violently denied during the war.

French Film Culture

For the French director and theorist Jean Epstein, who was a doctor and scientist, the camera was not a simple tool like the brush was for a painter. He thought of the camera as a “metal brain”, an instrument of revelation, just like the telescope and the microscope. It had insight and knowledge beyond normal human perception. Epstein’s first book is called Bonjour Cinema (Hello Cinema), while a later book was called The Intelligence of a Machine.

On a theoretical level, he presented the elusive concept of photo/génie (photo, the Greek word for light and genie as both magic and genius). He argued that it was the very essence of cinema that made film fundamentally different from the novel and dramatic theatre. He experimented with light as energy and movements of all kinds, in nature, the formation of crystals, and the movement of water, the sea especially, and also human and modern mechanical movements. So, editing became a means for exploring movements of all kinds, very different from montage thinking of the Soviets. For him, a story had to be told cinematically through these dynamic manifold movements of which human movement was but one component. He focused on the importance of light for the medium – electricity was relatively new. He said that, “the value of the photogenic is measured in seconds … the photogenic is like a spark that appears in fits and starts”. There is a heightened sense of time as intensity that is utterly ephemeral, always changing like life itself. These silent filmmakers are calibrating seconds.

Epstein developed a theory of the close-up—its powers of transformation through magnification of micro movement, converting a face into a landscape. Sergei Eisenstein also theorised the close-up, but differently, as a profound transformation of scale as a metamorphic power that derails habitual solid perception. They were internationalists, aware of each other’s work and followed Hollywood cinema closely because they found it very dynamic, (they loved Chaplin above all for showing the revolutionary power of laughter) but were devoted to exploring the expressive powers of this new technology differently as Europeans.

On a national practical level of the film industry, photogénie is concerned with creation of a specifically French style of film-making, one that resists the hegemony of American films in the marketplace. So this avant-garde cinema was the mainstream French industrial cinema of the 1920s working towards product differentiation in the market.

The organisation of film clubs in France in the 1920s by Epstein and others is one of the key moments in the development of a Film-Culture with a capital C, cutting into the traditions of high-culture. This French tradition has a continuous history from that time up to now through the institutions they created, certain journals like Cahier du Cinema still functioning. It developed a tradition of film criticism by critics. The French Cinematheque, which started in the 1930s by Henri Langloise, still exists. It’s a great film archive and a place where films are programmed in such a way that one can study the history of cinema there, hear lectures by filmmakers and historians, and study the work of a director in depth. So one could say that France has a highly evolved film culture that is over a 100 years old because of the film institutions created from the 1920’s on.

Soviet Film Culture

The Soviet filmmakers of the ‘20s also created a powerful film culture despite the state control of the arts. They wrote criticism, theoretical texts, and polemical manifestos about montage. They all accepted montage as the key cinematographic act; but how exactly it was to be done was the subject of heated debate. They have the oldest film school in the world, established with a visionary curriculum formulated by major filmmakers. Eisenstein was also a great teacher as were many other filmmakers. His theoretical and other writings form a vast body, only a small fraction of which is translated into English.

Montage is a term taken from engineering, of fitting pieces of machinery together. But it’s much more than a technical term; it’s a concept. Film does not flow like a river. Photogram, cut, break-flow system. The French word for editing is in fact montage. But the Soviets converted it into a film-concept which encodes ideas. Used creatively, montage has the power to stimulate thinking with images and not only with words. It’s this idea of montage editing as a conceptual construction that is developed by the Soviet theories of montage.

Shot one plus shot two is not shot three. Why? Because the result is not visible, it happens in our mind, which forms a mental image, so it has the power to be less logical, wildly imaginative even. There could be a flurry of ideas depending on how shots one and two are constructed, to maximise conflict, the idea of SHOCK as the modern urban sensation on so many levels, but for them an aesthetic concept as well.

In the silent era the idea of shock was central to Eisenstein’s thinking on montage as a dialectical process, thinking cinematically of the Marxist notion of the dialectic. Debates raged among filmmakers because they didn’t agree on HOW montage should be done. Eisenstein vs. Vertov; Eisenstein vs. Pudovkin. Eisenstein laughed at Pudovkin by saying that he made films with bricks, his shot is like a brick, homogeneous, inert, without rhythm, one brick on top of another, like on a wall. Vertov thought Eisenstein didn’t take montage into the deepest layers of a materialist exploration of the image of social reality and of the medium itself, because he created fictional narratives. But Eisenstein thought of the shot as a montage cell, as in cell biology revealed by the microscope. The shot is, for him, a dynamic process.

They discussed the power of montage in stimulating thought about historical processes and political processes. Formal ideas, theoretical concepts, aesthetics, and politics were integrally connected in their way of thinking about and making film. This is their formidable legacy to us. Aesthetics, which derives from the Greek word Aisthesis, means sense perception. It is not something added on like icing on a cake but constitutes the art object and stimulates our processes of sense perception and thereby thought. The audio-visual structure of film makes it a powerful multi-sensory mode of experience. Film Culture is inseparable from thinking because for them film was offering us a new sensorium—a new brain and a body.

Australian Indigenous Film Culture

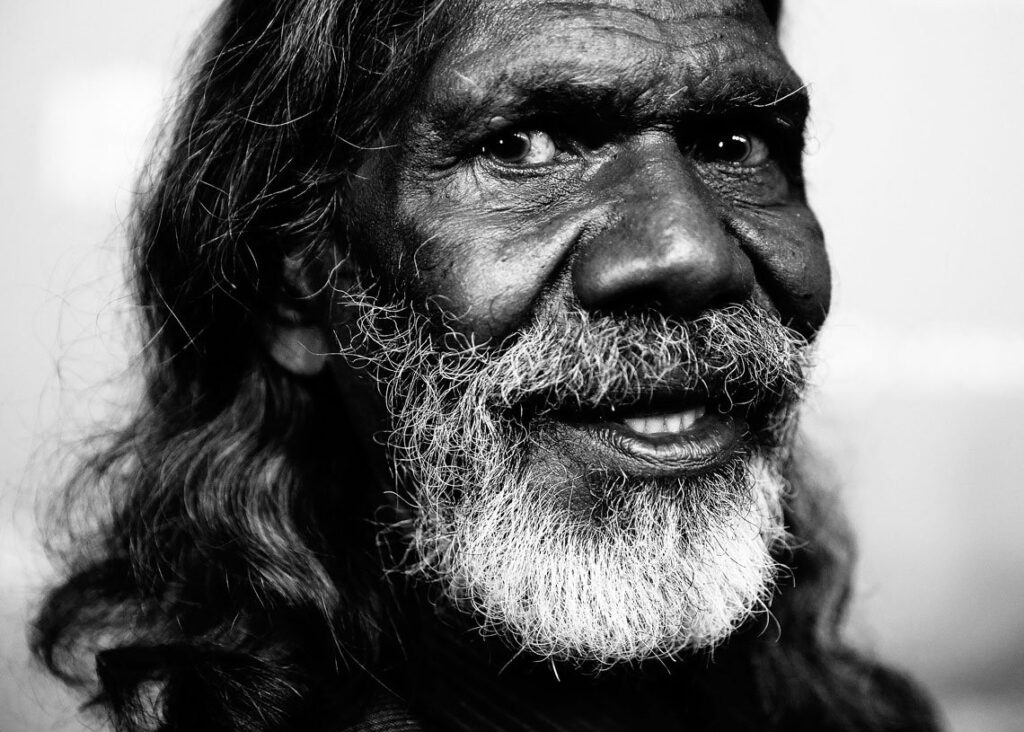

Australian indigenous film culture began unusually through a British film called Walkabout (1971, Nicholas Roeg) with the Australian aboriginal actor, David Gulpilil in a leading role. He spoke several of his own languages but not English when he was chosen to play the role. In life, Gulpilil was a tribal Aboriginy who was a hunter and dancer, and a singer and a painter too. It was a rare occurrence for white Australians, and indeed for me, to see a black person in an internationally celebrated film, which is now a classic. Over a career of 50 years Gulpilil, who died recently, helped to create a robust indigenous film culture by becoming a cherished national icon who opened indigenous culture and historical experience to European and other non-indigenous Australians, in a profound way.[iii] Soon after the film, what he said in his very first interview on national radio is a lightning strike that illuminates a violent colonial history. He was our mentor, barely 20 years of age, educating us when he said simply and movingly, “See culture is… you got your culture, I got my culture. Anyone got culture. I keep my own culture”,[iv] meaning both law and lore, myths, stories, and legends that have sustained Australia’s First Peoples for millennia.

David Gulpilil at the opening night of the Sydney Film Festival on June 8, 2016 (Photo by Brendon Thorne / Getty Images)[v]

Through indigenous political activism over many years the State took responsibility in establishing an Indigenous Department in the larger Screen Australia organisation for promoting indigenous story-telling and history. Now over 25 years old, systematic training and production was made possible for generations of indigenous filmmakers and actors, including workshops for script writing. Now there is a TV channel, NITV, dedicated to indigenous affairs including film. A sophisticated body of scholarly and critical writing has developed ways of understanding the culture of Australia’s First Nation Peoples, who have the oldest, continuous, living culture in the world going back to some 65 thousand years, with civilisational story-telling traditions transmitted orally and in painting and ritual.

Rachel Perkins, the daughter of the civil rights leader Charles Perkins, is a celebrated senior indigenous filmmaker and public intellectual, who has worked in documentary, feature films, and important collaborative TV series, and also heads a production company supporting innovative projects. This is an ongoing success story of an alternative Australian film culture which has matured, achieving a global profile. A mere 3% of the total population, indigenous people have been filmed by colonial anthropologists, almost from the very beginning of film, and have been subjected to violent scientific scrutiny with the camera by the postcolonial State. They have finally taken up the camera to create their own images and sounds of a land and a people who have survived political violence. They are now offering us a deep history of this ancient island continent so that its future as a multicultural nation with a shared future may be realised.

Pathi’s Australian connections are strong, doing a PhD at Monash University, on the cinema of Ray, Ghatak, and Sen. Monash University’s Dr. David Hanan published a fine tribute to him when he died, appreciative of the fact that a distinguished Lankan filmmaker came over to study with them.

To summarise:

- A film culture can be created by a cinephilia, a belief that film in its collective reception, when carefully curated and programmed, can generate discussion of ideas—ethical and political.

- A journal culture through blogs or whatever means of writing film criticism must be encouraged. This is an essential requirement for a film culture with any sense of continuity. Training in the skills of visual and sound analysis should be part of this practice. There should be an encouragement of a diversity of ways of writing about film avoiding academic exclusivity and jargon, always opening up avenues for new connections across disciplines. I get the impression that there are many young male film critics doing fine work and I am wondering if there are as many women film critics in Sri Lanka today. Where possible use of all three languages and an interest in films across ethnic differences should be encouraged.

- The idea of the ‘Alternative’ should not simply be oppositional in a reactive sense, but rather develop its own positive agendas and political and other passions. Debates and disagreements must be freely aired, without fear and intimidation, so that critical thinking is given free play.

- A curiosity about the histories of cinema and of contemporary cinema should be cultivated, widening the understanding of how diverse films are globally and what a rich history they have. Within the ethos of an authoritarian State, it would require imagination and some ingenuity to nurture spaces where thinking about film becomes irresistible as a collective project.

- All of this should in turn encourage filmmaking and experimentation; and now with relative ease of accessing technology rather cheaply; filmmaking, thinking with images, even on a small scale can be supported despite the lack of state support and training.

I want to remember just a few names essential to my PhD work in the 1970s on Lankan cinema. There was Jayavilal Wilegoda and Charles Abeysekera from the ‘50s writing reviews of pre-Rekava films, calling for a national cinema that was true to our social conditions. As someone raised as a Roman Catholic, I want to acknowledge the Sri Lankan branch of the International Catholic Film Organisation (OCIC) headed by Reverend Father Ernest Poruthota, and the film awards they gave, and the several film indexes on Lankan films they published—a collector’s item because some of these films might have perished by now. Their 35mm projection facilities were made available to me over three years to study over 100 films. Ashley Ratnavibushana of Sinesith magazine, I remember with gratitude, supporting my research into Sinhala cinema.

I’ll end with a current example of why I think there is a powerful alternative film cultural ethos in Sri Lanka. It may be sporadic, but it does exist. An exemplary framework for a deeply informed discussion of a film yet to be released has been created by Professor of Fine Arts, Sarath Chandrajeeva in his two-part article written in both Sinhala and English, in Annidda and The Island respectively, on the cultural and historical background to Asoka Handagama’s Alborada. Everyone interested in thinking about an alternative film culture should read it because of the exemplary way it generously prepares an ethos, a space, for understanding the 1920s Ceylonese multi-cultural historical context of the film.

One could also read the long Sinhala poem written by Chandrajeeva as a tribute to the nameless person or character at the centre of the film, the young woman of Telugu descent and a Dalit (formerly known as ‘Sakkiliya’ caste), who cleaned Pablo Neruda’s toilet each morning and who, by his own admission, he had raped. It’s called, “Dawn Lament or the complaint of a nameless toilet-cleaning woman” (Arunodaye Vilapaya: Handuna nogath kasala sodanniyakage paminilla). In this poem we hear her speak.

This is the power and joy of a film culture where the unpredictable can happen because film stimulates passionate thought and there are creative artists and critics, like Sarath Chandrajeeva who devote a great deal of research, time, energy, and care to make these thoughts accessible to us cinephiles in an appealing manner without any rancour.

Let’s conclude by listening to Pathi’s voice again from an interview in the Australian film journal Senses of Cinema by Brandon Wee (2003).

Brandon Wee: In Sri Lanka you have been called a “rebel with a cause.” How do you feel about this label?

Dharmasena Pathiraja: It’s really metaphorical. One should not think of the artist as a rebel who is going to bring about objective change. The rebel is within you. So, you rebel not against the world but against yourself. In Asian societies particularly, one struggles to capture a reality in rebellious terms. One recreates realities through a rebellious search for freedom of expression from the tired old forms, the familiar ways of capturing reality, and the experiences of social reality. This rebellion has to come from within one by way of confronting familiar truths.

Laleen Jayamanne is a film scholar, critic, and theorist based in Australia. She is the author of The Epic Cinema of Kumar Shahani (Indiana University Press, 2015) and The Poetic Cinema and the Spirit of the Gift in the films of Pabst, Parajanov, Kubrick and Ruiz (Amsterdam University Press, 2021). In 1985, she made the film, A Song of Ceylon, as a dramatic and daring response to Basil Wright’s The Song of Ceylon.

This is an adaptation of the Dr. Dharmasena Pathiraja Memorial Lecture delivered by Laleen Jayamanne on his fourth death anniversary on 28th January 2022, organised by the Department of Fine Arts, University of Peradeniya.

References

Bennett, Tony Lawrence Grossberg, and Meaghan Morris. (2005). New Keywords: A Revised Vocabulary of Culture and Society. Oxford: Blackwell.

Chandrajeeva, Sarath. (2021a). “Beyond the fiction of Alborada”. The Island. 04 December 2021. Accessed 14.02.2022. Available at https://island.lk/beyond-the-fiction-of-alborada/

——— (2021b). “Beyond the fiction of Alborada – II”. The Island. 15 December 2021. Accessed 14.02.2022. Available at https://island.lk/beyond-the-fiction-of-alborada-ii/

Farmer, Robert. (2010). “Epstein, Jean”. Senses of Cinema (Issue 57) (December). Accessed 14.02.2022. Available at https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2010/great-directors/jean-epstein/

Williams, Raymond. (1958). Culture and Society. New York: Columbia University Press.

——— Williams, Raymond. (1976). Keywords. London: Croom Helm.

[i] The reference Jatalayan invokes the three Jatila brothers, Uruvel Kassapa, Nadee Kassapa, and Gaya Kassapa to whom the Buddha delivered one of his earliest sermons. On his search for Truth during his time as Prince Siddhartha, the Buddha had spent considerable time studying their approaches.

[ii] Niganta is a reference to Nigantha Nātaputta, known as Mahavira in Jainism. He was one among the Six Eminent Teachers of Buddha’s time, and practiced four-fold restraint i.e. abstaining from using cold water which is endowed with the principle of life (jiva); avoiding all evil; washing all evil away; and being suffused with the sense of evil held at bay. Staunch believers of ascetic living, this school was in direct opposition to the Middle Path that the Buddha advocated. The reference in both cases (Jatalayan and Nigantayan) is to the supposed misguided nature of such practices, and the harm they inflict upon the ‘true’ nature of Buddhist inquiry and ethics.

[iii] ABC. (2004). “Gulpilil”. (26 June). Accessed 14.02.2022. Available at https://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/archived/radioeye/gulpilil/3374810

[iv] National Film and Sound Archive of Australia. (1978). “‘I KEEP MY OWN CULTURE’ – DAVID GULPILIL’S EARLY LIFE”. Accessed 14.02.2022. Available at https://www.nfsa.gov.au/collection/curated/i-keep-my-own-culture-david-gulpilils-early-life

[v] Photo of David Gulpilil reproduced from Jayamanne, Laleen. (2020). “The Many Faces of David Gulpilil”. The Monthly (14 July). Accessed 14.02.2022. Available at themonthly.com.au/blog/laleen-jayamanne/2020/14/2020/1594685727/many-faces-david-gulpilil#mtr