World Class City

Abdul Halik Azeez

“Here is the City Paranoiac. All these long centuries, growing over the country-side? like an intelligent creature. An actor, a fantastic mimic. Pointsman! Counterfeiting all the correct forces? the eco-nomic, the demo-graphic? oh yes even the ran-dom…”

Thomas Pynchon,

Gravity’s Rainbow

I built Colombo in a dream. Clean streets, spotless floors, spotless walls, and well-dressed and polite sales staff. No pavement hawkers screaming in your ear. No poor beggars asking you money for a tea. No dust and smoke clogging up your face. No uncategorisable petti kadeys. No more looking askance at parippu wadeys, and contemplating Chinese rolls and vegetable rotties while nearby, the kottu shop attacks your ears. Instead I walk along shiny streets deciding between juicy burgers and penne pasta. There are no more dubious ‘Gift Shops’ or ‘Fancy Mahals’. Instead I purchase beautifully designed, pastel shaded household objects fit for the most minimal living room in Japan, finally saying goodbye to the kitschy paraphernalia with which my mother has occupied the hall cabinet. I drive my Suzuki in air conditioned comfort from my air conditioned apartment to my air conditioned office. In the evenings I jog in public spaces where everything is shiny marble and the trees are kept in their own little enclosure, their wildness contained.

I see an old man with a yellow plastic bag that says COLOMBO CITY OF 2020, and then in cursive script running below that, “in Sri Lanka”. Red and black stars decorate the bag. He wears a sarong, rubber slippers, and is digging in his shirt pocket for change when the Pettah to Panadura bus screams to a stop, the conductor hollering on top. He runs to get onboard. Last week I saw another bag which said COLOMBO 2020, the cursive script here read “wonder of Asia”.

Maybe this man should have had that bag because it had a beautiful skytrain cruising away from the Lotus Tower and a group of other skyscrapers. This skytrain would not have hosted a screaming conductor. It would never have screeched to a stop, endangering the lives of its potential customers. The cursive script on that bag also made more sense.

On the top of the One Galle Face mall, in the Star Trek Park, a balcony looks over Galle Face. Teenagers and twenty-somethings, dressed in their best clothes, stand around and Tik Tok. They are careful to occupy little corners and cul-de-sacs, so that on the camera it looks like they are in a private space. We try our best to ignore them and pass them and go to the balcony and look at the blazing sunset. The glorious armed forces are performing the ceremony to carefully bring down the national flag with the agitated lion fluttering in the breeze. We look beyond as the sun subsides and wonder if we will be able to swim off the artificial beach that will soon border the Port City.

The flag ritual has gathered an audience of tourists. An ahikuntakaya has set up shop. Unsolicited, he has taken out his cobra, which is now vaguely moving to the rhythm of his flute as his monkey watches from nearby. The people closest to him are a couple, he is brown, she is white. The woman thinks it is animal abuse. But the man wants to give the gypsy some money. He extends a hand with 50 rupees on it. But the gypsy says, “more money sir”. The brown man speaks in Sinhala, “I’m Sri Lankan, take it”, but the gypsy refuses “what can I do with 50 rupees?”. The brown man curses and walks away.

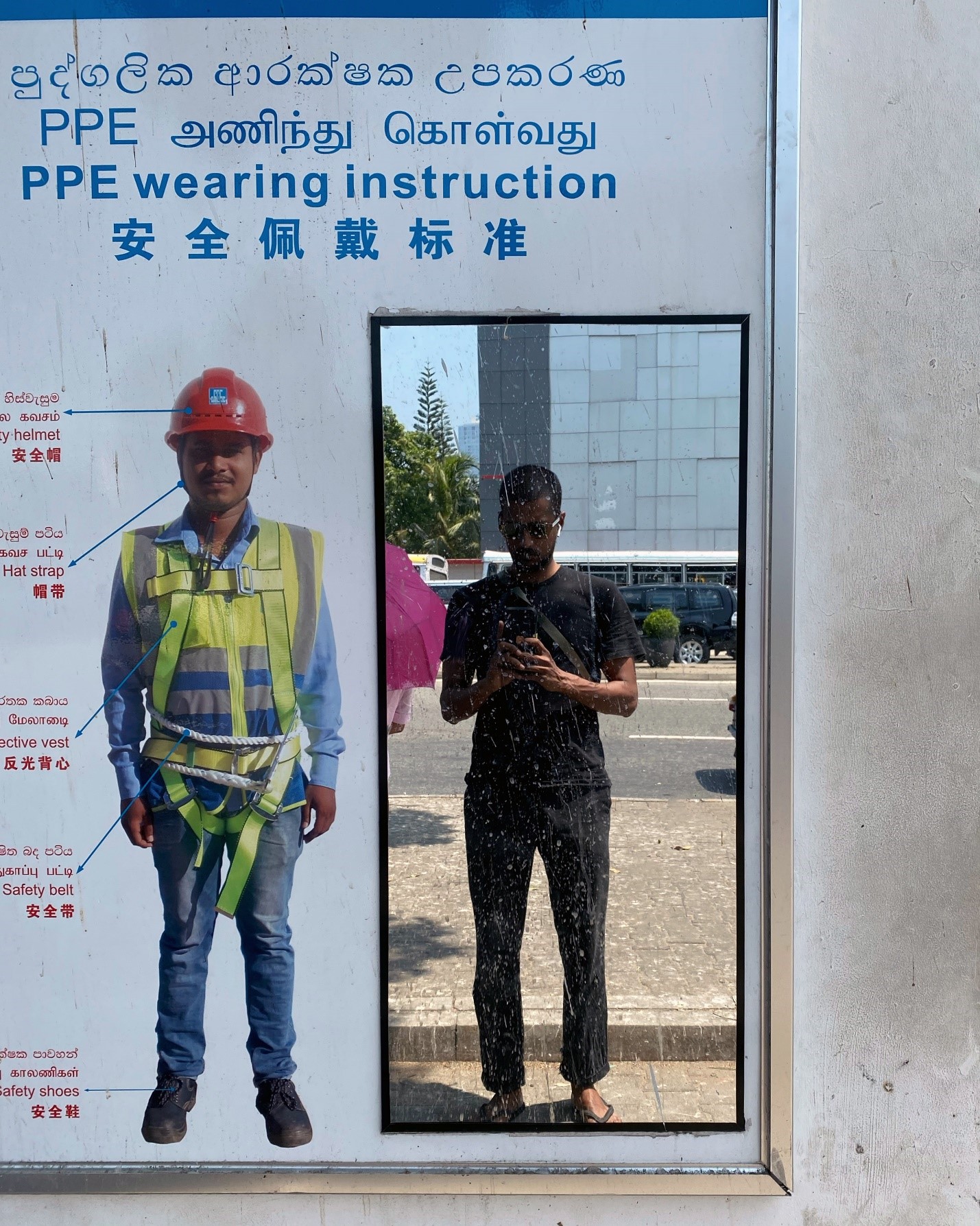

Last week I was walking around in the car park behind the One Galle Face Mall, and I saw a yellow construction helmet on the ground. It was poetically impaled on an iron rod, like the head of an enemy soldier put there as a signal, rotted so much that it had slid down to the ground. I took a picture of it. It will look good on my Instagram. I take pictures of things I see in the city. I am documenting Colombo, giving it a dystopian feel. Dystopia differentiates me from your average swimsuit wearing, restaurant and resort patronising, cultivated looking influencer.

Less than a kilometer away, in Slave Island, there is a gym called ‘Island Fitness’, it is inside a ramshackle house next to the rail tracks, you have to climb up some rickety stairs that will really test the balance of your calf muscles. Leg workout done, you are inside a space with red cement floors and cream walls covered in posters of Flex Wheeler and Arnold Schwarzenegger. Powerful non-Sri Lankan men encourage you with glistening smiles as you sweat in the tropical heat lifting rusted weights. Your dehydrated muscles are nourished by a non-complex-carb based diet and motivated by a fever dream of six packs and bulging pecs, Lambhorginis and Hameedias shirts. Trains occasionally whizz by the window outside; if you reach you can probably touch the hands of the people who will soon be leaning precariously from the doors, one-handed, sweaty, slippery grips barely holding on to slick stainless steel bars as they take the glorious risks of the competitive sport of rush hour footboard commuting.

In the evening I sit on an unused natami cart at the corner of Church Street. This corner of Slave Island is so fertile that buildings that grow here and tower up to the sky, far higher than the lone palm trees left of the fauna that once made the Dutch call this area a “garden”. Hundreds of workers labour tirelessly to feed their hungry roots while billboards in Hindi try to sell them mobile data packages. A drunk Imtiyaz, who has been sitting next to me on the cart all this time, tells me that all the Chinese workers buying groceries are actually prisoners who are here to pay off their debts. But the workers aren’t just Chinese. They come in droves, from all across the region, to feed the hungry roots of the concrete trees.

Suddenly I remember how a while ago, a doctor friend told me how a man with a mangled hand was sent to her. It required surgery and six months of physiotherapy to fix. But they wanted him back at work in two days. A shift is finishing and construction workers are walking about with plastic bags, buying groceries and other essentials. I see them foregrounded against the old De Soyza building, built by Charles De Soyza almost a century ago.

Charles De Soysa built a fortune partly by selling alcohol to freshly minted wage labourers and indentured workers in the 19th century. He was hailed as one of Sri Lanka’s greatest philanthropists through his charitable foundations, and was so rich he became famous across the Raj. He built this building now foregrounded against the skyscraper forest looming behind it. It is slated to be destroyed, and a group of activists have been trying their best to prevent that from happening. It is such a poetic sight; this turn of the century Art Deco building with trees growing out of its (y)ears, contrasted with the stark glass and concrete of contemporary corporations from all over the world. I am anticipating at least 200 likes for it.

Later that night, I meet Dimitri at Cheers, he has been wanting to meet for a while. Cheers is by @itswellabeach and we chat as the waiter serves us mixed seafood fried rice and Lion Lager. A man from the next table comes over to ask for a light. After he interrupts us a total of three times, he gratefully insists that we also take two of his pungent cardamom cigarettes, which we do out of politeness. Dimitri is not looking happy. As we finish our first pitcher he begins to tell me about his crushing debt. He had been working at a big 5 star hotel but had quit and just started his own business. But now the Coronavirus, which has almost entirely wiped out tourism, has hit him in the most sensitive of places. “How much do you have to pay every month?”; “one lakh”. He has taken out loans to buy a car, and to pay for his wedding. And now he will soon drive for Uber to try and make ends meet.

I have a daily commute of 6 hours back and forth to my office in Colombo. One day my boss announces that he wants to start a new culture in the office, a culture driven by health, fitness, and “proactive ownership of organizational objectives”. He tells me to get a gym membership at Power World because he has noticed that I am looking unhealthy. I ask him for a raise to pay for a room in Colombo. He laughs. It is hot tonight and I am not sleeping well. At least I don’t have to go to work anymore. Say all you want about the virus bringing back nature, but I wish these birds would shut up so I could sleep past 5 a.m. for just one day in my new life.

“World Class City” was originally commissioned by the International Center for Ethnic Studies (ICES) as part of “Home and Belonging: A Multimedia Portal of Loss, Revival and Connections”. An expanded set of images accompanying the piece can be viewed online at momac.lk.

Abdul Halik Azeez is a visual artist and writer with a background in journalism and linguistics. Over the past decade he has worked closely on the issue of post-war gentrification in Colombo, exploring it through various mediums such as photography, moving images, and installations. More of his work can be viewed on abdulhalikazeez.com or instagram.com/colombedouin.