James Brow was a British anthropologist who drifted from the nascent counter-culture of early 1960s London, to the mid-1960s West Coast of the USA, where he found a remarkable life partner in Judy, and a setting more congenial than the damp England of James’s upbringing; an England still tightly constrained by its obsession with class. In the US, James also found a vocation as a researcher and teacher of anthropology. He and Judy carried out fieldwork for two years in villages north of Anuradhapura between 1968 and 1970. James then took up a position at Swarthmore and completed his PhD. When he failed to get tenure at Swarthmore – a mercy as he saw it in retrospect – he moved to the University of Texas at Austin, where he stayed until his retirement in 2007. In 1983 he returned to Sri Lanka with Judy and their two children for the fieldwork that would go into his second book, Demons and Development. He returned for a final visit as the organiser of the Anuradhapura Conference in July 1984, exactly a year after the 1983 pogrom.

In this piece I will try to do three things.[1] Firstly, I will provide a personal assessment of a fine anthropologist, friend, mentor, and frankly lovely human being. Secondly, I will discuss the Anuradhapura Conference and use it as a source of reflection on the decline in studies of agrarian change from the 1980s onwards, in Sri Lanka, but also in many other parts of the region. In that respect I will be, I hope, continuing a conversation initiated by Urs Geiser and his excellent contribution just over a year ago at the start of this series (Geiser 2023). I am in broad agreement with most of the central points in Urs’s argument and therefore don’t feel the need to repeat them in detail here, not least, as I could not hope to reproduce Urs’s own depth of experience and breadth of reading and understanding on these issues. Instead, I can present in close focus as it were what it felt like to be working in a moment when earlier ways of interpreting rural change, whether through the empiricism of Edmund Leach, or by way of the Marxism of Newton Gunasinghe, were supplanted by what Geiser calls “critical” theoretical perspectives. Thirdly, this is one of a number of more or less autobiographical pieces I have written in the last year or two, doubtless originally in part a response to imminent retirement. Although it may not be obvious here, I have been also inspired by Pierre Bourdieu’s writings about the need for a sociological self-analysis as one way in which to better understand how the objective conditions in which researchers work silently impinge on the questions we ask and the problems we think important (Bourdieu 1990; 20-21; 2008). In this case, why was agrarian change self-evidently such a central theme of late 1970s and early 1980s social science here, and how and why did it fade away?

Biography 1: School, Navy, Oxford, London

James Brow was born in 1937 and grew up in Ipswich. In terms of a chronology of anthropologists of Sri Lanka, James sits midway between his mentor, Gananath Obeyesekere and his close friend Jock Stirrat. But in terms of his upbringing and education, it means he straddled the social and cultural changes of the mid-20th century. He scored a century for his minor boarding school at cricket, and he was in almost the last cohort to be called up for national service after school, serving two years in the Navy. As a flight navigator on an aircraft carrier, he had a close-up view of that bizarre late imperial foray, the 1956 Suez crisis. James’s memories of his time in the Navy were surprisingly warm, and at that point his life might have been expected to stay on a predictable English middle-class track – university, one of the professions (a solicitor or a teacher), a house in the suburbs. But it didn’t.

From the Navy he went to Oxford where he studied modern history, graduating in 1960. He once mentioned that he had been an exact contemporary at Oxford of Perry Anderson, who as a theoretical young Turk wrested control of New Left Review from E. P. Thompson and his allies in the early 1960s. What were Anderson and his fellow young leftists like, I asked? Far too posh to have anything to do with someone like me, James replied. Anderson had gone to Eton, James to a lesser private school: then as now, the gulf between them was vast. This passing comment reveals James’s keen sense of the hidden injuries of class, even between different grades of private education – you can see why Sri Lanka might make a sort of sense to him – and his lifelong disdain for hierarchies of class and caste. James’s son Geoffrey traces some of this to his time in the Navy, when James found himself inducted as an officer, when equally qualified conscripts who hadn’t had a private education found themselves stuck in the ranks. Geoffrey also suggests this may be a clue to explain the draw of anthropology, and especially the draw of the impoverished Dry Zone communities James spent so much time with between the late 1960s and early 1980s.

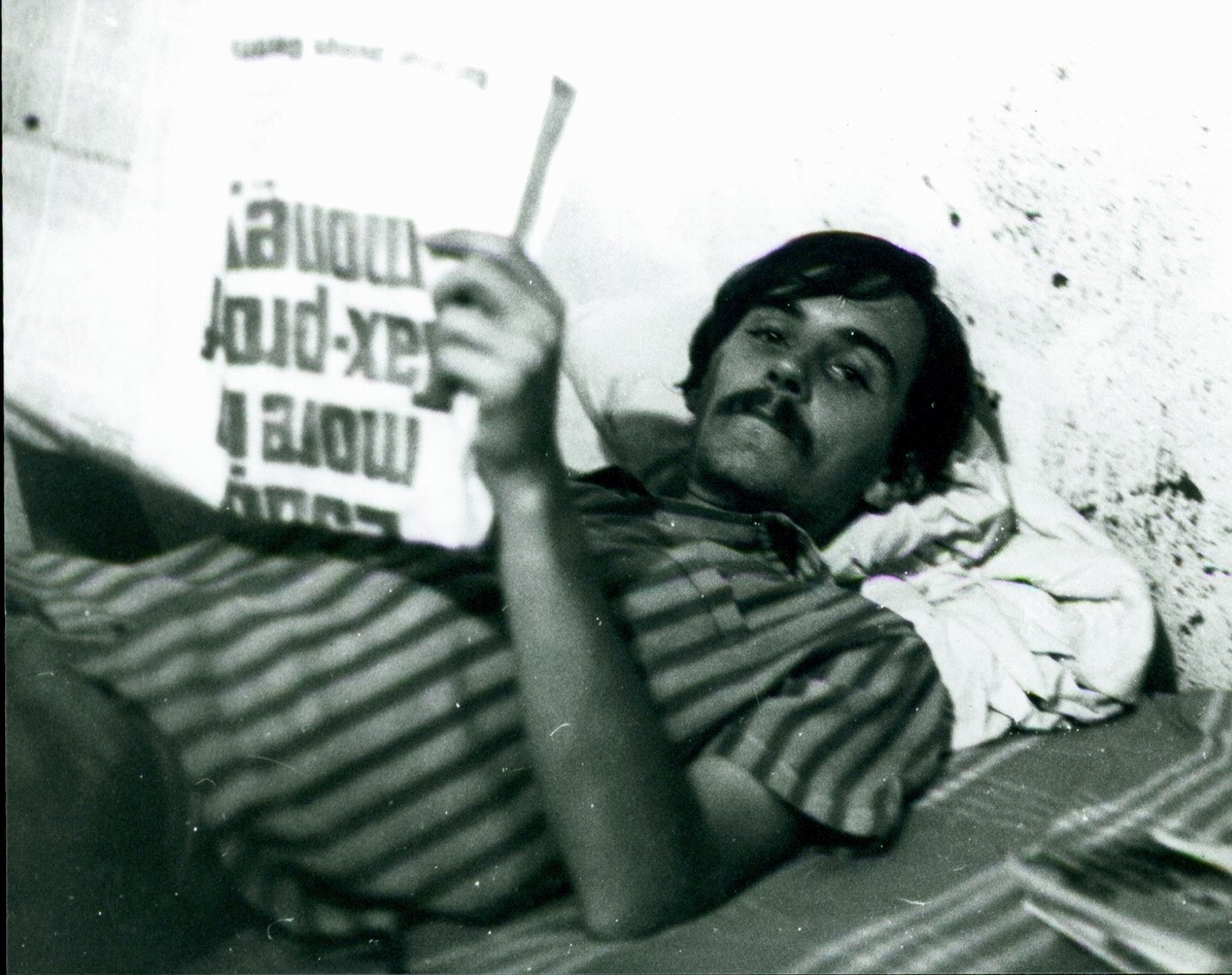

Certainly, James’s life after Oxford veered completely off the tracks of bourgeois respectability. At Oxford he’d played drums in jazz groups, and after graduating he appears in the background in various histories of the 1960s London counter-culture. He lived in a legendary flat close to Paddington Station belonging to John “Hoppy” Hopkins. Hoppy was involved in setting up the first UK underground paper, International Times, or IT as it was known, as well as the London Arts Lab. Hoppy’s flat was an intensely social space, with constant jazz playing, some weed being smoked, people reading aloud from Beckett and Flann O’Brien. At one point the neighbours complained about the constant laughter coming through the walls.[2] Although there are countless photographs in circulation of the scene at Hoppy’s flat, the only picture of James from this period is one magnificent shot of him playing the bass drum on an early 1960s Aldermaston march in protest against nuclear weapons (reproduced in Miles 2008: 92-3).

Biography 2: Seattle, KRAB, Judy, anthropology

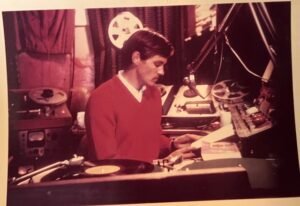

Around this time, Judy, who was a few years younger, was sharing a house in San Francisco with future members of the Grateful Dead. James sidled his way across the Atlantic via a cousin in Toronto. His first job in the US was as a waiter in a Greenwich Village coffee shop. He then appears in Seattle, sometime around 1963, in the company of a friend called Lorenzo Milam, who had started one of the first “listener-supported free form” radio stations using the FM band, Radio KRAB. Judy worked at the station, which was run on a shoestring and combined experimental music with high-minded spoken word programmes. Their first meeting is the stuff of family legend, as recounted by their daughter Ranjini:

My mom was already in Seattle. She was from Palo Alto, CA and had been admitted to Berkeley at age 16. She did a year there and then dropped out and floated around. She was living in Seattle on a houseboat and managing a radio station called KRAB. My Dad had a friend named Lorenzo who he was staying with in Seattle. My mom and Lorenzo were friends. The story is my parents met at a gas station. Lorenzo cruised up in a convertible with handsome British James in the passenger seat. My mom happened to be there and Lorenzo introduced James, saying he had just arrived in town. My mom took one look at him and said “he can stay with ME” and that night she cooked him dinner on her houseboat and he never left.

Station KRAB has a special place in US radio history and a lot has been written about its early days. In an online archive there is a link to a TV documentary from 1964 about the station, which features a scene with James, Judy and Lorenzo on James and Judy’s houseboat, and another scene with James reading out listeners’ letters to Lorenzo.[3]

It’s impossible to think of James without Judy – and vice versa. They were to stay together for over 50 years, until Judy died, three years before James, in 2019. When I first met them, I was puzzled by the contrast in personal style: where James was quiet and reticent, Judy was loud and uncensored. In my naivete, I thought this must be difficult for James to deal with, but I soon realised he loved Judy precisely because she would do and say the things his English politesse prevented him from doing. It was a great union.

In 1964, while they were both working at the radio station, James and Judy joined the University of Washington’s graduate programme in anthropology. This was where Gananath Obeyesekere had just completed his own PhD, and although he had no formal supervisory role in James’s program, he served as mentor and, with his wife Ranjini, friend throughout the years that followed.

In 1966, James and Judy spent a summer in the Canadian northwest collecting material for Judy’s master’s dissertation on the history of a First People’s group called the Shushwap. Then in 1968 James learnt he’d been awarded a National Science Foundation Fellowship for fieldwork in Sri Lanka. He told me that the day they got the news, it happened that the Duke Ellington Orchestra were playing in Seattle. He and Judy went to celebrate, and Judy, being Judy, struck up a conversation with the band in the intermission. A few years earlier, (as I’m sure all Colombo residents remember), the band had visited Colombo as part of the State Department tour that inspired Duke’s Far Eastern Suite, playing a gig at the racecourse (before it was a shopping arcade). Somehow the conversation turned to the snake life of Sri Lanka. “Yeah,” growled Johnny Hodges, possibly the most beautiful saxophone player ever, “Them polongas [Russell’s vipers] are real motherfuckers.”

Biography 3: Fieldwork, Swarthmore, Austin

James and Judy stayed in Sri Lanka from June 1968 to June 1970, living and working in Kukulewa, the largest “Vedda” village in Anuradhapura district. In the second year of the fieldwork, the Brows expanded their focus to include the whole network of villages – 45 in total – that identified as Vedda in the district. To do this they used questionnaires, and enlisted the help of students from Colombo university. I’ll return to that first study in a minute, but for now I want to cover the rest of James’s biography up that return trip in 1983.

In 1971 James was appointed Assistant Professor at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, and three years later he defended his PhD in Washington. The revised version of the PhD was published as Vedda Villages of Anuradhapura: The Historical Anthropology of a Community in Sri Lanka in 1978 (Brow 1978). By then James had learnt that he had been turned down for tenure by Swarthmore, but he was able to get a new, as yet, untenured position in Texas in 1979. Tenure followed in 1982, and promotion to full Professor in 1997, at which point he was in the midpoint of a long spell as department chair. James’s second book, based on the 1983 fieldwork, Demons and Development: The Struggle for Community in a Sri Lankan Village appeared in 1996. He published a steady stream of articles between the mid-1970s and the late 1990s. His last article appeared in 2009 in a festschrift for his old mentor Gananath, edited by H. L. Seneviratne.

James was, by all accounts, a great teacher. His former student Mike Woost:

He was just a wonderful and amazing teacher, in the classroom and one on one. Students highly respected him for his command of theory and his ability to help students formulate their research topics. He was on dissertations committees of students going everywhere in the world to do their fieldwork: Palestine, Peru, Mexico, India, Ecuador, Brazil, Egypt to name a few. Until I came along, he had no one going to Sri Lanka for fieldwork.

After Mike, who completed his PhD in 1990, James’s only other Sri Lanka student was Sandya Hewamanne, who has written movingly about her debts to James and to Judy in various social media posts over the years. In the tributes posted, and the conversations I have had with his former colleagues, there is a strong sense of a very collegial colleague, a team player who looked after everyone on his team. But there is also a sense of someone who looked out especially for the more vulnerable – the junior colleagues, women, minorities.[4]

Vedda Villages of Anuradhapura

I’m now going to talk briefly about James’s first book, before moving into the first person to talk about James’s 1983 fieldwork, and then the 1984 Conference. I’ll try to end with some observations about the present, but these will not be especially surprising. In Vedda Villages, James never explains quite why he chose this particular topic, though it’s pretty easy to guess. Kukulewa, where James and Judy based themselves, is about 30 kilometres east of Anuradhapura, and not so far from Edmund Leach’s field site, Pul Eliya (Leach 1961). The group identified as Veddas in this part of North-Central Province bear no traces of hunting or jungle existence. They are a group of impoverished cultivators, speaking Sinhala, religiously Buddhist, but endogamous and happening to be known, by themselves and by others, as Vedda. Because of the restrictions on marriage outside the community, James calls them a “caste”, justifying this by their use of the word variga in their self-descriptions. There are traces of that peculiar institution, the variga court, which provided Leach with so much of his raw material in Pul Eliya, but in the Vedda case the court had long been in decline and doesn’t possess the importance Leach attributed to it in the early 1950s.

The first chapter of Vedda Villages (which is my personal favourite) is a long essay on the history of the category Vedda, and its use and misuse in colonial ethnology. Here James comes close to a thorough deconstruction of the modern idea of the Vedda as isolated primitive descendants of the original inhabitants of the island, preferring instead a more relational and flexible understanding of how the category is used in practice. This is followed by core chapters on the village and the state, land categories and kin groups, and occupations. These to some extent work within the paradigm established by Leach in his earlier study, but the chapters that follow burst out of the confines of the village study, tracing the processes by which new villages are founded, merge and die, over time. The book is written with great clarity. The maps and diagrams are beautiful. The argument is deft and always intelligent. In terms of the tradition to which it obviously belonged, the caste-kinship-and-land studies of Leach, Yalman and Tambiah, Vedda Villages was a late 1970s state of the art example.

There are, I think, four points in the book where James pitches arguments that might be taken up in the future. One is the chapter on the very idea of the “Vedda”, which anticipates a lot of more recent scholarship on colonial taxonomies and indigenous categories. The second is an argument about landlessness which coalesces towards the end of the book. Leach in his more polemical moments railed against depictions of landlessness as a problem in rural Sri Lanka, arguing that many of those apparently landless were simply sons waiting to inherit from their fathers. This wasn’t always the case, even in the evidence presented in Pul Eliya. As things stand, cross-cutting ties of kinship, the availability of chena cultivation, and the opening up of former Crown land, all serve to mitigate the emergence of hard distinctions of class. But the increasing monetisation of relations will inevitably erode some of those ties and so it is possible that class relations will begin to emerge more visibly in the near future (Brow 1978: 217-19). This is the problem James addressed in a series of papers he published after Vedda Villages, and it provided the rationale for his return visit in 1983. But then he was to discover that the threat to community was not so much money as politics, and this is the theme of his second book.

But the other points with which the book ends feel less fertile for future argument. There is a long resume of the debates and disagreements among Leach, Tambiah and Yalman about the working of Sinhala kinship. James’s summaries of these tortuous debates are judicious and wise, but even as I originally read them around the original time of publication, I had a sense that these debates had run into the ground. And then the final part of the book makes a case for the need to frame an analysis of social action in terms of the meaning attributed by the actors themselves. We have reached the question of the interplay of material and symbolic factors.

1983, Colombo, Anuradhapura

In January 1983, James returned to Sri Lanka, accompanied by his 11-year-old son Geoffrey. Judy joined them a few months later with their daughter Ranjani. In James’s own description of his project, he had been concerned after the PhD with the question of the articulation of modes of production and class formation, but he was also interested in probing deeper into how people in the midst of change actually understood their situation – an issue glossed by the word ‘consciousness’. And he was also interested in the question of community. In short, James had become some kind of Marxist – but a Marxist in the lineage of Raymond Williams and the British social historians, rather than the French structural Marxists (who were more influential in late 1970s social science in Europe).

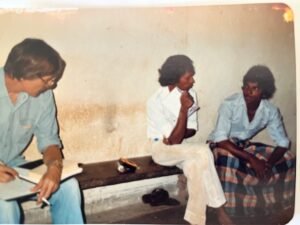

Somewhere around this time, I met the whole family at the anthropologists’ lodging of choice in Colombo, the determinedly seedy Ottery Inn. We became friends and kept in close touch for the duration of James’s stay. The plan was for James and Geoffrey to settle in Kukulewa, the central village in his earlier fieldwork, but conditions were harsh, there had been drought, and they retreated to a newly built house they rented in Anuradhapura. Kukulewa had been an early beneficiary of Premadasa’s Village Awakening programme, and a new model village, called Samadigama, had been built nearby. Premadasa himself came to inaugurate the new village, the houses were allocated on party lines, and the village split into two bitterly opposed factions. James had engaged an excellent field assistant, P. G. Somaratne, a Colombo sociology graduate who had worked closely with Newton Gunasinghe. At first James and Somaratne worked together, carrying out a census and gathering methodical data on change, but as time passed, Somaratne took on most of the ethnographic work and James stayed back in Anuradhapura and wrote. I’ll talk a bit more about what he wrote later.

Not long after she arrived, Judy learned that her mother had been diagnosed with terminal cancer; she returned to the US with the children, while James stayed on until October 1983. Mike Woost remembers being caught up in the July violence with James in Colombo.

I was with James in the summer of 1983, and we walked through the streets of Colombo during the riots of July, making our way back to the Ottery (I wonder if that establishment is still there?). Dreadful memories. After we finally got back to the Ottery, James intimated that he would never return to Sri Lanka. So, I was surprised when he did actually go back for the Conference.

A lot happened in July. Judy and the children left. James found himself in the middle of the violence. And in Kukulewa, a woman called Seelawathie started to be possessed by a god, who had things to say about the divisions that had sprung up in the village. Now everyone wanted to talk about the issues of community and change that interested James so much. I visited James in Anuradhapura during those final months of his fieldwork. By then, he and Somaratne had settled into a routine. Somaratne spent the days in Kukulewa keeping up with the developing supernatural soap opera that focused on Seelawathie and village politics. He would come to James’s house in Anuradhapura in the morning to update him on the latest events. James would absorb what he had been told, and then return to the manuscript he was writing, which was effectively a first draft of Demons and Development. It was written in his distinctive, rather beautiful semi-italic handwriting, and by the time I visited, was about 30 or 40,000 words. He lent this working draft to me to read. It was beautiful – clear and gripping, almost novelistic in its structure. I was amazed that he was able to write something so compelling, while the events he was writing about were still unfolding in the village. His explanation was that he wanted to get as much of the writing done as possible before his return, as he knew the distractions of everyday academic life would make writing much harder back in Austin.

This is perhaps the point to pause the narrative in order to say a little bit about my relationship with James. Oxford where I completed my PhD prided itself on its culture of supervision by benign neglect. When I moved there from Chicago, one of the academic staff told me, “You probably won’t find many people to talk to, but at least we’ll leave you alone to get on with your work”. This they certainly did. In the absence of any substantive supervision, I relied heavily on support from my fieldwork peers like Mark Whitaker, Liz Nissan and Colin Kirk, and some older anthropologists like Jock Stirrat and James Brow.

Looking back from the present, I begin to realise just how important James was to me. Intellectually, we were both very much on the same page, and despite the fact that he was infinitely senior to me in career terms, our relationship was always egalitarian. We exchanged drafts of papers and chapters through the 1980s. If James’s writings were strikingly clear and unpretentious, so too were his comments and criticisms of other people’s work, but the comments I received, in their quantity and tone, were above all infused with an ethos of kindness and generosity. Through our meetings at workshops and conference panels we gradually assembled the papers that made up Sri Lanka: History and the Roots of Conflict (Spencer 1990a). In an academic world not dominated by moral exemplars, James stood out as a really good person. In many respects, my own PhD thesis, and the book (Spencer 1990b) that came from it, can be read as less assured versions of James’s Demons and Development: in both cases we’d set out to document a process of emergent class formation in the countryside; in both cases we’d discovered that the bigger story was about the place of the state in village affairs; and we both aspired to write something that would be accessible to readers beyond a narrow audience of professional anthropologists, by bringing real people and their stories into our writing.

Symbolic and Material Dimensions of Agrarian Change (the Anuradhapura Conference)

We now enter the part of my story which rests on the shakiest ground. The Anuradhapura Conference on agrarian change, which James co-organised in 1984, was more or less the first time I presented my own work in front of a seasoned academic audience. I was absurdly anxious and absurdly excited. If I had to rely on memory alone, the next section would be five paragraphs of me reproducing the buzzing in my ears that accompanied me through the days of the Conference.

The Anuradhapura Conference was a manifestation of that generosity I just mentioned: a well-funded international meeting in which most space was to be given not to senior luminaries who had been flown in to pontificate, but to junior researchers with fresh material of their own to share. The Conference itself was co-organised by James, with Gananath Obeyesekere and (I think) Norman Uphoff. Thirteen papers were presented, 11 on Sri Lanka. Of those, three were by researchers still working on their PhDs, and another six by researchers who had only just completed. Most of the presentations were the outcome of some sort of larger village study. The funders covered the travel costs of the international participants – which I managed to stretch to cover a three-month follow-up fieldtrip to the site of my earlier research. Newton Gunasinghe, who didn’t bring a paper himself, was a livewire participant in all the discussions.

I was unnerved to discover that (as I saw it) Mick Moore and I had independently written the same paper – mine on ‘Representations of the Rural’, his on ‘The Ideological History of the Sri Lankan Peasantry’ (Moore 1988) – and then I was just as quickly reassured by Mick’s generous response to the coincidence. It was my first meeting with Mick, and with Tudor Silva, Tamara Gunasekera, Serena Tennekoon and Siri Hettige. For me, I gained immediate access to an expanded peer group of like-minded researchers, and to a wealth of comparative material which enabled me to see those things in my own field context that had seemed unusual and atypical, but which turned out to be common but relatively unreported aspects of rural life.

Examples would be high levels of informal migration based on relatively easy access to plots of crown land, and a rapid post-1977 turn to cash-cropping for the island-wide market. Another example, which would dominate much of the discussion, was what presenters often referred to as politicisation – the penetration of village life by party-based factions and the place of patronage in the production and reproduction of inequalities. It took a semi-outsider, Ron Herring, whose own field experience of politicisation in CPI-dominated Kerala had meant Marx study circles and earnest discussion of primitive accumulation, to point out that what we were calling politicisation in rural Sri Lanka was not quite as obvious as it appeared.

One temporal marker which has the authentic feel of the early-mid 1980s is the awkward place that gender occupied in the discussion. Only two of the attendees were women – Serena and Tamara – and only Tamara presented. This is particularly striking because 20 years earlier, Ralph Pieris had criticised Leach for presenting an unreflexively male view of village social life (Pieris 1961). The participants were uneasily conscious of the deficit, and there were a couple of extended discussions of women working as migrant wage labourers, but most of us were aware there was a systematic problem here, even if no one had a convincing response to it. That was the early 1980s in a nutshell.

There was quite a bit of discussion of class. I remember long and rather directionless discussions of the different words villagers might employ – did madhyama differ from samanya, and other imponderables. In a letter with instructions for revision and publication after the Conference, we were urged to be at least consistent within our papers in the terminology we used, and if possible, to think about the potential difference between local categories and more rigorous classifications based on access to the means of production.

If the title of the Conference – ‘Symbolic and Material Dimensions of Agrarian Change’ – suggested a potential stand-off between Marxist and non-Marxist theoretical positions, that’s not how I remember things playing out. The tension in the discussions that I recall was between what I would now call interpretivist and positivist positions. This was a moment of epistemological rupture within anthropology: a couple of months earlier in the US, another group of (almost entirely male) scholars had convened to discuss experiments in ethnographic writing. Their deliberations were to appear two years later as the influential volume Writing Culture (Clifford and Marcus 1986), a volume that would at once blow open the conventions of ethnographic writing, and usher in an arsenal of post-structuralist literary criticism to accompany the move. (Of course, most of the participants in Anuradhapura didn’t identify as anthropologists, so some of the argument about the goals of ethnographic writing might well have seemed to be rather missing the point. Others will have very different memories, I’m sure.)

The Conference was also held exactly one year after the July pogrom and just under a year before the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) attack on Anuradhapura in May 1985. Many of us felt the drift to civil war had to be addressed even if we didn’t know quite how. My paper and Mick’s both discussed Sinhala nationalist framings of rural change and the place of the rural in the nationalist imagination. I’d like to think that we may have helped propel Serena Tennekoon, who was just about to start her doctoral field research, into her brilliant work on the ideological labour J. R. Jayawardene’s government was putting into the Mahaweli project (Tennekooon 1987). The other work which feels to me like an indirect product of the Anuradhapura Conference – even though he wasn’t actually present – is Mike Woost’s (1993, 1994) work on village politics and village nationalism in Moneragala District.

The plan was always to produce a volume from the Conference which went beyond the usual bunch-of-papers format. Joe Weeramunda, the most senior of the younger Sri Lankans present, would co-edit with James. Funds were found to bring Joe to Texas to work alongside James (as well as funds for some of the other Sri Lankans to carry out follow-up fieldwork). We were issued with advice and instructions for revising our papers. Along the way, we lost a number of participants but gained four papers that had not been presented at the Conference – overview pieces by James and Mick, and new pieces by Newton and Piers Vitebsky. And then? And then, nothing happened. No publisher seemed to be interested and eventually the editors wrote to us to suggest we find other homes for our pieces if we wanted to. Mick’s article went into a journal, and I incorporated mine into the revised book version of my thesis. And then? And then, out of the blue, we learnt that a publisher had been found after all. The volume appeared from Sage in 1992, eight years after our meeting.

Demons and Development and the Decline of Village Studies?

By the time Agrarian Change in Sri Lanka finally appeared, the intellectual tide had firmly turned. In his Introduction to the SSA volume Capital and Peasant Production in 1985, Newton Gunasinghe comments disparagingly on the genre of the village study:

These “village studies” are a contribution to our knowledge, only in one sense; whereas earlier, no one has known about the existence of Mudville, now anyone so inclined, can read the monograph and can come to know something about its geography, location and inhabitants. But they do not make a theoretical contribution to the understanding of the socio-economic processes at work in our countryside (1985: vii).

After several decades when some version or other of the village study dominated Sri Lankan sociology and anthropology, the number of new studies almost completely dried up from the mid-1980s. We didn’t lose sight completely of the issue of agrarian change, but as Geiser shows in his review of the decades after the 1980s, our sources are thin and in general rather uncritically framed. Geiser is also clear that Newton’s alternative to the village study – more rigorously theoretical Marxist framing of change – did not represent the solution to the problems that cluttered the conversations in Anuradhapura. Instead, we needed more attention to gender and intra-household dynamics, just as we needed a way to map and assess the impact of state and non-state agencies which were such an important of the rural scene by the 1980s.

To some extent, James’s second book, Demons and Development: The Struggle for Community in a Sri Lankan Village, which finally appeared in 1996, did just that. It was not a book about agrarian change per se, which might explain its absence from Geiser’s otherwise very comprehensive review, but it does sketch in the key features of recent agrarian change in Kukulewa in a short section early on – particularly the expansion of wage labour and the transition from traditional subsistence-oriented swidden to new forms of cash cropping. It also has a lot to say about the intrusion of national politics into village affairs, and perhaps for the first time in a Sri Lankan study, it allows the individual voices of villagers to come through loud and clear. The book tells the story of the bitterness of village politics and of the efforts to invoke gods to heal the divisions caused by the new housing allocation. The voices belong to both men and women, so as well as individual actors, the book makes a start in challenging the male-dominated accounts of the past. It’s a compelling read – James’s clarity of analysis and writing is at its best.

The book reminds us above all of an old point from Clifford Geertz: “anthropologists don’t study villages … they study in villages” (1973: 22). The village is a convenient point from which to look at the world; it isn’t to be confused with the world. In Demons and Development James showed us what we could learn about politics and development, the state and nationalism – as seen from the perspective of one, out of the way village. I’d suggest the perspective remains valuable, so for example, if the current crisis is above all a crisis of poverty and food security, as I think it is, that can be studied just as well from a village as from anywhere else. In revising this paper, I was asked what James’ work might tell us about the current agrarian crisis. The answer is simple: there is no substitute for prolonged empirical engagement, and no excuse for ignoring the voices and perspectives of the people most affected by the crisis themselves. If that disturbs your sense of theoretical certainty, so be it – there’s work to be done.

In a review in a leading anthropology journal, Sasanka Perera (1998) praised the book, but with three caveats: the long delay between fieldwork and publication; a certain closeness in places to middle-class romanticised versions of the traditional village community; and what he saw as an unnecessarily heavy theoretical introduction. The first criticism has some justification. I had read a draft of the central part of the book in 1983, and James had rehearsed the various theoretical arguments in articles published in the late 1980s. At that time, ethnographic writing which gave access to individual voices was relatively rare – Scott’s Weapons of the Weak (1985) and Willis’s Learning to Labor (1978) are the obvious comparisons. By the time Demons appeared, James’s style seemed less radical. The theoretical discussion which Sasanka complained about is only a few pages long, and is in fact a very lucid, indeed helpful, guide to questions of hegemony and consciousness, by way of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, E. P. Thompson and Raymond Williams, Antonio Gramsci, Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe. Getting from James’s experiences in 1983 to the clarity of the story he told in 1996 involved a great deal of hard theoretical work. On the question of romanticisation of lost community, I tend to side with Sasanka. My own view was that villages had always been divided, but had found other ways to work through the divisions; modern party politics had provided a new medium for the expression of division and the growing importance of state resources – like the model village provided for Kukulewa – raised the stakes in all disputes.

This was a rare but persistent point of disagreement between us. James knew my criticisms but was unmoved by them. Now, nearly 30 years later, and thinking about this in terms of James’s biography, I think it all makes more sense. His whole journey, from school through the navy, Oxford, bohemian London, jazz, to the houseboats in Seattle and anthropology, finally found a point of rest in these impoverished and marginal communities in North Central Province. If there’s a theme linking the stages in that journey, it’s a flight from hierarchy and snobbishness. James’s attachment to the ideal of rural community was based in his own experience of it in Kukulewa in the late 1960s.

Years later, on a visit to Austin in 1989, I sat with James on his back porch as dusk fell. He lived just outside the city. His house was on a small rise and as we looked out at the arid empty landscape stretching to the horizon, the Brows’ Sri Lankan rescue dog snuffling around us in the brush, James turned to me and said, “You know, sometimes looking out from here, it feels just like the Dry Zone”. I close with that mental picture of my friend and mentor, James Brow, a truly lovely man.

Jonathan Spencer FBA is Emeritus Professor of South Asian Language, Culture and Society at the University of Edinburgh.

References

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Trans. Richard Nice. London: Polity.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 2008. Sketch for a Self-Analysis. Trans. Richard Nice. London: Polity.

Brow, James. 1996. Demons and Development: The Struggle for Community in a Sri Lankan Village. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Brow, James. (Senior editor, with Joe Weeramunda). 1992. Agrarian Change in Sri Lanka. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Brow, James. 1978. Vedda Villages of Anuradhapura: The Historical Anthropology of a Community in Sri Lanka. Seattle: University of Washington Press. (Reprinted 2011 by Social Scientists’ Association, Colombo.)

Clifford, James and George E. Marcus (eds). 1986. Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Geertz, Clifford. 1973. ‘Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture’. In The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Geiser, Urs. 2023. “Reflections on Critical Agrarian Studies in Sri Lanka”. Polity. Vol. 11, Issue 2 (December 2023): 40-48, available at https://ssalanka.org/reflections-on-critical-agrarian-studies-in-sri-lanka-by-urs-geiser/

Gunasinghe, Newton. 1985. ‘Introduction’. In Charles Abeysekera (ed). Capital and Peasant Production: Studies in the Continuity and Discontinuity of Agrarian Structures. Colombo: Social Scientists’ Association.

Miles, Barry. 2008. Peace: 50 Years of Progress, 1958-2008. London: Anova.

Moore, Mick. 1989. “The Ideological History of the Sri Lankan ‘Peasantry’”. Modern Asian Studies. 23 (1): 179–207.

Perera, Sasanka. 1998. “Review of Demons and Development: The Struggle for Community in a Sri Lankan Village”. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 4 (3): 577–579.

Pieris, Ralph. 1961. “A Sociologist’s Reflections on an Anthropological Case Study”. Ceylon Journal of Historical and Social Studies. 3: 144-156.

Scott, James C. 1985. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press.

Spencer, Jonathan (ed.). 1990a. Sri Lanka: History and the Roots of Conflict. London: Routledge.

Spencer, Jonathan. 1990b. A Sinhala Village in a Time of Trouble: Politics and Change in Rural Sri Lanka. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Tennekoon, N. Serena. 1988. “Rituals of development: the accelerated Mahaväli development program of Sri Lanka”. American Ethnologist. 15 (2): 294-310.

Willis, Paul. 1978. Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs. London: Routledge.

Woost, Michael D. 1993. “Nationalizing the local past in Sri Lanka: histories of nation and development in a Sinhalese village”. American Ethnologist. 20 (3): 502–521.

Woost, Michael D. 1994. “Developing a nation of villages: Rural community as state formation in Sri Lanka”. Critique of Anthropology 14 (1): 77-95.

Notes

[1] Acknowledgment: This is a slightly revised text of a talk at the ‘Critical Agrarian Studies’ seminar of the Social Scientists’ Association (SSA) in Colombo on 13 March 2024. One of the most important intellectual events in my life occurred in Anuradhapura 40 years ago (23-27 July 1984). The Conference was in large part the work of James Brow; and this appreciation of him was first mooted when James died in early 2022. I would like to start by thanking Balasingham Skanthakumar and Upul Wickramasinghe, and others at SSA, not least Chulani Kodikara whose idea I think this partly was, for providing me with this opportunity to pay tribute to an old and much missed friend, James Brow, but also for providing me with an opportunity to reconnect with SSA itself. When I was trying to turn my own experience in Sri Lanka in the early 1980s into a PhD thesis, while also trying to make better sense of the rush to war, one of the first and most important books that I got hold of at that moment was the 1985 SSA collection, Ethnicity and Social Change in Sri Lanka. In 1991, when I was able to return after seven years away, I was invited to speak at SSA, and some of the friendships forged on that occasion have been among the most important friendships of my academic life. I must give especially warm thanks to James and Judy Brow’s children, Geoffrey and Ranjani, and James’s student Mike Woost, who have supplied me with memories, stories and pictures that fill in many of the gaps in my own understanding of James’s quietly remarkable life.

[2] Adam Ritchie interviewed by Adam Blake, 2 June 2015, available at https://internationaltimes.it/tales-of-hoppy-1/, accessed 9 March 2024. Another long-standing friend from those days was Ben Palmer, a pianist who went on to become a sculptor, after a spell as Eric Clapton’s road manager.

[3] The Theory and Practice of Radio Station KRAB: A Film Documentary About KRAB, Seattle – 1964, available at https://www.krabarchive.com/the-theory-and-practice-of-krab-a-film-documentary-circa-1964.html, accessed 9 March 2024.

[4] Towards the end of James’s long stint as chair, one of his most brilliant junior colleagues, the Basque feminist anthropologist Begonia Aretxaga died of cancer. I had friends who were very close to her, and I remember how James and Judy featured very prominently in their stories of Begonia’s illness, and also in subsequent efforts to mark her passing and preserve the spirit of her work.