After 31st March, 2022, Sri Lanka’s politics is no longer what it has been. It seems to have entered a qualitatively new phase. It is still too early to say anything definite about the true magnitude and future directions of this newness. Its basic character and dimensions, however, are quite clear. The ‘direct democratic’ action of the group of citizens who protested in front of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s residence in Pengiriwatte, Mirihana, has given rise to outcomes even they would not have quite anticipated. It has shaken the very foundations of an autocratic-authoritarian regime that was, up until now, perceived to be as strong as an immovable rock.

With that spontaneous action of citizen protest, a new people’s movement has emerged, openly demanding some fundamental changes in the existing political order. In a flash, it has brought into direct and passionate political action a hitherto silent and politically passive body of citizens from a wide range of social backgrounds. They are reclaiming their lost political agency as citizens. Shaking the foundations of the Rajapaksa government is something that the country’s political parties could not do for nearly three years. Yet, through their voluntary, spontaneous, and direct political action, Sri Lanka’s citizens have now done that. While insisting on the resignation of the President and the Prime Minister, and all the MPs in Parliament, it also demands some fundamental changes and transformations in the overall system of government in Sri Lanka.

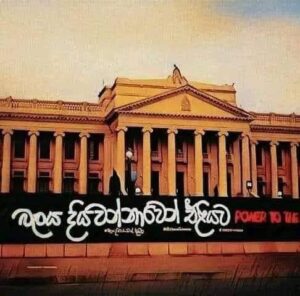

Thus, this is a rare moment of Sri Lankan citizens’ political awakening. They are now asserting their public duty to the common good of the larger political community. Young citizens in large numbers are spearheading this new movement of resistance and political hope. This is Sri Lanka’s long awaited moment of democracy.

This marks an extremely important milestone of a process geared towards reviving and preserving democratic politics in Sri Lanka. Against a backdrop of the quality of Sri Lanka’s representative democracy in steady decline, the direct entry of citizens into active politics in an important intervention. It marks the inauguration of a new politics of critique, resistance, and democratic rebuilding in Sri Lanka. This is all the more significant at a time when traditional institutions of democracy such as Parliament and the judiciary have been mere onlookers of a steady decline of the country’s political life.

It is therefore essential to assess the importance of this movement in order to appreciate its political potential and strengthen its constructive outcomes.

Political Dimensions

The first positive dimension of the protest movement is that it has brought to an end one institutional consequence of Sri Lanka’s representative democracy: the notion of ‘passive citizenship’. I have heard many of our political activists lamenting that “Sri Lanka’s democracy has produced voters, but not citizens.” According to this complaint, the Sri Lankan voters would fall prey to the false promises and blatant propaganda of politicians around times of elections, cast their votes, come back home, and then fall into a long political sleep. What we see now is that the citizens have shed this habit of political passivity to come forward and reclaim their role as politically active and responsible citizens. Politically alert and vocal, citizens have begun to congregate at public gatherings and chant slogans of protest and resistance in unison to expose the misrule and misdeeds of a regime that has been showing an incredible degree of insensitivity to hardships that the people in the country have been undergoing for months. This collective and direct political action of citizens amounts to the opening up of a social space for direct democracy and the inauguration of a new tradition of vigilant, active, and assertive democratic citizenship in Sri Lanka.

A second positive dimension has to do with the weakening and perhaps dismantling of the ideological hegemony so far maintained by the Rajapaksa government and their Sinhala nationalist cronies. This owes largely to heightened political consciousness on the part of citizens. The communalist ideological control that the Rajapaksas had established over the Sinhalese society has close parallels with India under Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Sri Lanka’s citizens have set an example for the Indian citizens too to return to their democratic, secular, and multi-cultural roots, breaking up the ideological straitjacket of ethno-religious communalism. The morning following the Mirihana protests, the President’s Media Office attempted to arouse Sinhalese communalism by making direct parallels with the ‘Arab Spring.’ It failed. Not only do citizens at the protests not use communally divisive slogans, they also denounce the deployment of such reactionary ideologies. Thus, the present protest movement is not only multi-class, but also multi-ethnic, multi-cultural, and diverse in its social bases and ideological orientation.

This signals another important feature of the present moment: the economic and political crisis has opened up new space for building a ‘democratic public’ with a political consciousness transcending ethnic and religious communalism. The demos of Sri Lanka have returned, reclaiming their place in the country’s politics, challenging the corrupt political oligarchs.

Fourthly, the protests highlight the message that the decaying political system including the specific form of democracy we have, needs far reaching reform, and the country’s government and political structures as well as institutions need refashioning. Citizens have also lost trust in the undemocratic political institutions as well as the greedy, corrupt, inept, and unreformable authoritarian political elites. The present wave of protests by the citizens embodies a mixture of political reactions to this state of affairs—disillusionment, despair, loss of trust, anger, and of course political hope for a fresh beginning. That is why Sri Lanka’s citizens have now decided to take democracy into their own hands through direct political action.

Fifthly, the citizens’ protests that spontaneously began to erupt throughout March 2022 should not be viewed as an isolated development despite their suddenness. They are the culmination of a series of protests against the government that broke out throughout last year. Tamil citizens of the North seeking justice, rural farmers expressing anger against the President’s fertilizer policy, and the public sector teachers and plantation workers demanding higher wages inaugurated different phases of this wave of citizen resistance.hen came sporadic protests – evening candle-light vigils — by urban, middle class citizens at road intersections in Kohuwala, Ratmalana, Rajagiriya, Pita Kotte and in a few towns outside Colombo. What seems to have really tested the patience of Sri Lankan citizens during the past few weeks is the absolute failure of Sri Lanka’s President and his government to ensure the basic everyday survival needs of the people – electricity, cooking gas, diesel and petrol, food and essential commodities, regularly and at reasonable prices. The Rajapaksa administration’s failure to govern is also its failure to run the State, an elementary duty of an elected ruling class. It pushed the Rajapaksa regime into an unprecedented crisis of legitimacy, seriously damaging its moral right to rule, despite the veneer of constitutional legality it still commands. The inability of the rulers to empathise with the suffering of the people caused by their own misrule, is obviously what transformed people’s sense of despair and torment into collective political anger and direct action. In fact, the month of March led to a moment in which the people of Sri Lanka saw an irreparable breach of the symbolic social contact between the rulers and the ruled.

Finally, the citizens’ direct action is not merely a protest movement. Slogans and demands of the ‘protestors’ carry alternative visions and ideas of politics, democracy, and governance. They call for re-inventing Sri Lanka’s parliamentary democracy in such a way that the Parliament, the electoral process, and cabinet government are freed from the debilitating control exercised by the corrupt political class and their bureaucratic, business, and nepotistic cronies. They are also demanding political parties to begin to represent the interests of the Sri Lankan people, and not their financiers, political brokers, corporate allies, or family members. They seek a Parliament and a new generation of parliamentarians who will honour the people’s expectations for a genuinely democratic political order in which politicians are accountable to the people and directly answerable to their electors.

Thus, the call for such fundamental reforms to be affected to Sri Lanka’s decayed system of politics and governance is no longer confined to radical Left-wing or civil society groups who traditionally raised such issues in the public domain. It is now part of a powerful democratic call by young citizens too. The people rejecting those parties and leaders that do not meet their reform expectations. The citizens of our society are demanding that political parties and leaders abandon the old cultures of electoral politics sustained on false promises, ideological manipulation, patronage networks, and ethno-religious communalism. Unless political parties reform and reinvent themselves, it would now be difficult for them to regain credibility, legitimacy, and even relevance.

In short, the doors have been opened to re-invent democratic politics in Sri Lanka, to usher in a qualitatively new stage of political development. The old order and its custodians are under severe pressure to give way to a new one. This is the most important message of the citizens’ political activism, with the youth at its core, that emerged on the evening of March 31st. In the past too, Sri Lanka’s youth have spoken politically, but not in the language of democracy. This time around, the youth are speaking politically, in the language of democracy, peace, and pluralism. Silently, they seem to have inherited and internalised, and saved for the appropriate moment, the finest legacies of Sri Lanka’s democracy and democratic modernity.

The challenge now is to continue to keep those doors open, nourishing the citizens’ struggle, and work to ensure that a process of political transformation is set in motion. This is a serious affair, and one that urgently requires discussion and debate. The remainder of this essay is devoted to laying some groundwork for such a discussion to take off.

Agency to Resolve the Crisis

As we have already seen, citizens are no longer satisfied with band aid solutions or fake promises. The capacity of the established political parties to deliver anything else is under serious questioning particularly by the young citizens. What their critique tells us is that finding solutions to Sri Lanka’s present crisis is beyond the capacity of the political class and political parties that have been part of the problem. This is the political essence of the slogan, “We don’t want all 225!” [parliamentarians].

It is true that those who were part of the problem cannot be part of the solution. Yet, the question remains: who has the agency to provide and champion solutions through a reform programme? Can the protesting public do it on their own, without an organisational arm or some form of minimum institutionalisation of their campaign? Shouldn’t a broad coalition of citizens and citizens’ associations emerge to take the struggle forward? These are questions that cannot be ignored by the citizens who participate in the campaigns and its well-wishers as well.

The signs at present are that the protest campaign will intensify in the coming days and weeks, with increasing numbers of citizens joining it. Power cuts, shortages of gas, diesel, petrol, kerosene, food and medicine, rising inflation, falling living standards, and arrested education of children will continue to haunt public life in the months to come. Solutions to the current economic crisis, which the government is likely to implement in partnership with the International Monetary Fund, will most likely have the potential to further hurt Sri Lanka’s poor, the working people, and the middle classes. No easy resolution of Sri Lanka’s grave economic crisis is even conceivable. Moreover, while the government is incapable of resolving the political crisis, not much can be expected from the other political parties either. This will lead to renewed frustration and anger on the part of the public, more aggressive protests, and greater potential of the protests spreading to other cities.

In other words, it is inevitable that there will occur, in the coming weeks, a sharp polarisation of forces, with an angered and politically fired up public on one side and an isolated government with diminished legitimacy to rule on the other.

There is also an on-going political deadlock marked by a protracted contestation between a regime which has lost its legitimacy to rule and a parliamentary opposition with no parliamentary strength to replace the regime. The main opposition parties — Samagi Jana Balavegaya (SJB), the United National Party (UNP), and the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) and Tamil National Alliance (TNA) — hardly have anything new or imaginative to contribute to finding a way out of the deadlock. They equally lack credibility or legitimacy among the protesting citizens. Can these opposition parties in the political mainstream do anything different from their parliamentary politics as usual in order to initiate a dialogue with the protesting citizens? It is indeed quite difficult for the protesting citizens and the mainstream opposition parties to build trust and discover a language of dialogue. What is likely to happen is the shifting of the sympathies and loyalties of many rank-and-file members and voters of these parties to the emerging citizens’ force.

Among the parties in Parliament, the one with at least a slight chance of winning public trust is the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP). However, if the JVP leadership continues to play it safe without deciding on a politically strategic stance at this juncture, they too might find themselves isolated from the protesting public. They have to make sure that their support for the citizens’ struggle is not linked to their electoral agenda.

Thus, there is some measure of discomfort and tension in the relationship between the citizens’ protest movement and the opposition political parties. It is due to the fact that the new movement has sprung up totally independent of the parties and is even rejecting the kind of politics that the latter have been identified with. This is not surprising in view of the fact that during the past year or so there has been a sustained conversation among some sections of the Sri Lankan citizens on the need for a broad, non-party and inclusive democratic movement of citizens to take the sporadic people’s struggles for social and economic justice forward. That movement has now emerged with no prior warning. The opposition political parties will be under pressure to reform or perish in the face of a new democratic challenge for which they have not been prepared. The JVP seems to be feeling this pressure quite intensely.

A Conundrum to Overcome

In this background, the conundrum faced by the public as well as political parties is this: can a voluntary citizens’ struggle under decentralised leadership, without an organisational network with other citizens’ associations and movements, and still awaiting a long-term strategic vision, continue to make sustained political interventions? Can it transform itself into a force with enough agency to deliver the kind of ‘radical’ political change – encompassing structural, institutional, and personnel aspects — as articulated by its spokespersons and envisioned in the key slogans used in the protest?

The same question re-emerges as follows: whether the President, Prime Minister, and the Cabinet resign or not, a political vacuum will certainly emerge in the coming days, because there are now two centres of power in the country; (a) the President, Cabinet, and Parliament, and the security apparatus on one hand, and (b) citizens in protest, occupying the Galle Face, and demanding the resignation of the President, Prime Minister, and members of the ruling family, on the other. Does a presently voluntary and spontaneous citizens’ movement have the capacity to step in to fill the inevitable political void? Is it necessary to think of a new kind of transitional, interim arrangement, until a new political order is born democratically and peacefully?

The point here is that the question of political power is certain to pose itself sooner or later. In his public address the other day, Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa hinted at the question of political power a few times. Being a leading member of Sri Lanka’s ruling class for a long time, Prime Minister Rajapaksa has sensed that what is at stake at present is political power. The protesting citizens have also been raising that question indirectly and unintentionally, and perhaps not as part of a conscious political strategy. The choice before the citizens’ movement now is the classic conundrum faced by social movements seeking political change: to remain an unconscious tool of history, or to be a self-conscious agency of political and social change?

The JVP’s Dilemma

These questions are pertinent not only to the young leaderships at the forefront of the protest movement of citizens. They are also difficult questions that the JVP needs to ask of itself.

The JVP also finds itself facing a dilemma in the face of on-going protests. The protests started independently of the JVP, and perhaps without even the JVP’s knowledge. The party has publicly claimed on a number of occasions that it had no affiliation with the protests and protestors. It is clear that the JVP has been over-cautious about the possibility of agents provocateurs engineering violence amidst protest action in order to pin all blame on the JVP and justify a crackdown by the State. Such an acts or acts would eliminate the dual threat of both an angry citizens’ movement and a rising JVP.

However, standing aloof from the protests will be politically costly for the JVP. One option before them is to positively respond to the critique of the dominant political order that the protesting citizens have been advancing and reform their politics, programme, and vision accordingly. The JVP now has the exciting option of learning the art of solidarity politics with movements that emerge outside their own template of radical politics, and forming transformative political alliances. This suggestion applies to the Frontline Socialist Party (FSP) as well, which has of late adopted a policy of openness towards alliances with other Left parties. The FSP seems to have worked out a flexible strategy to work in solidarity with the protesting youth constituencies.

The fact that the protesting public is rejecting all 225 in Parliament has difficult implications for the JVP. It should accept the political symbolism of that call. It denotes the frustration, sense of betrayal, and the anger the citizens have been expressing towards the political elites, parliamentarians, parliamentary democracy, institutions of representative democracy, and the decadent political institutions and political class. All parties including the JVP need to listen to the public critique of them, and reform accordingly. Anyone who does not, might have a rough future ahead.

The citizens’ movement, on the other hand, should ask itself two further questions: the first is whether it can, singlehandedly, resolve the political crisis it has exposed so powerfully? The class/social basis of the movement is the middle class. It is true that this class has become politically active and influential. However, it needs to ask itself a second – related – question of how it can link with the majority of the politically active people’s groups in the country: farmers’ associations, workers’ unions, professional groups, women’s groups, student movements, and the people of the North and East all of which are organised entities for social-political action. If the movement rejects established political parties, a very constructive option available is to work together with movements that have a long history of struggle against injustice and for citizens’ rights.

Obviously, the time is now ripe for a broad coalition of progressive and democratic citizens’ movements and communities in Sri Lanka. Its core constituency will certainly be the protest movement of citizens. Such a coalition will be able to address the question of political power, which has begun to enter the on-going political contestation between the government and the citizens.

The citizens’ movement will have to confront these difficult questions in the coming weeks. They are unavoidable; they require deep reflection and discussion leading to solutions as well as alternatives. This will invariably enable the citizens’ movement to move forward with greater conceptual and ideological clarity about its goals, directions, and strategies.

Jayadeva Uyangoda is emeritus professor of Political Science at the Department of Political Science and Public Policy, University of Colombo.